Volume 10, Issue 4 (12-2025)

J Res Dent Maxillofac Sci 2025, 10(4): 330-337 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.MAZUMS.REC.1401.14935

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Yahyapour K, Mollaei M, Alimohammadi M, Yaghoubirad S, Hadian H, Hosseinnataj A et al . Accuracy of Alveolar Bone Height and Thickness Measurements with Cone-Beam Computed Tomography in Presence of Stainless-Steel Crowns. J Res Dent Maxillofac Sci 2025; 10 (4) :330-337

URL: http://jrdms.dentaliau.ac.ir/article-1-934-en.html

URL: http://jrdms.dentaliau.ac.ir/article-1-934-en.html

Kosar Yahyapour1

, Melika Mollaei2

, Melika Mollaei2

, Mona Alimohammadi3

, Mona Alimohammadi3

, Sara Yaghoubirad4

, Sara Yaghoubirad4

, Hoora Hadian3

, Hoora Hadian3

, Abolfazl Hosseinnataj5

, Abolfazl Hosseinnataj5

, Atefeh Gholampour *6

, Atefeh Gholampour *6

, Melika Mollaei2

, Melika Mollaei2

, Mona Alimohammadi3

, Mona Alimohammadi3

, Sara Yaghoubirad4

, Sara Yaghoubirad4

, Hoora Hadian3

, Hoora Hadian3

, Abolfazl Hosseinnataj5

, Abolfazl Hosseinnataj5

, Atefeh Gholampour *6

, Atefeh Gholampour *6

1- Dental Research Center, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

2- Dental Research Center, Mashhad Dental School, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

3- Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology, Dental Research Center, Faculty of Dentistry, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

4- Department of Restorative Dentistry, Dental Research Center, Faculty of Dentistry, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

5- Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Health, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

6- Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology, Dental Research Center, Faculty of Dentistry, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran ,atefehgholampour70@yahoo.com

2- Dental Research Center, Mashhad Dental School, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

3- Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology, Dental Research Center, Faculty of Dentistry, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

4- Department of Restorative Dentistry, Dental Research Center, Faculty of Dentistry, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

5- Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Health, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran

6- Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology, Dental Research Center, Faculty of Dentistry, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran ,

Full-Text [PDF 399 kb]

(13 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (22 Views)

Full-Text: (5 Views)

Abstract

Background and Aim: Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) is a valuable imaging modality suitable for analyzing the hard tissue of the maxillofacial region. However, the artifacts caused by some dental treatments may reduce the image quality and lead to misinterpretations. The present study aimed to assess the accuracy of CBCT measurements in the presence of stainless-steel crowns (SSCs).

Materials and Methods: This in vitro experimental study was conducted on 4 sheep hemi-mandibles. First, gutta-percha points were placed on the buccal and lingual surfaces of the alveolar ridge, and bone height and thickness were measured with a digital caliper (direct measurement). Then, three CBCT scans were obtained as follows: The first scan was performed without placing the SSCs, as the baseline image; the second scan was performed after placement of one SSC, and the third scan was performed in presence of 3 SSCs. Red wax was used for soft tissue simulation. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22 (alpha=0.05).

Results: The findings revealed no significant difference between the direct measurement and the baseline image in terms of measuring the bone height and thickness (P>0.05). The difference between the baseline and scan image measurements in presence of one SSC was not significant (P>0.05). Furthermore, the accuracy of CBCT images did not decrease after the placement of 3 SSCs.

Conclusion: The Presence of SSCs did not decrease the accuracy of linear measurement of alveolar bone height and thickness. Moreover, increasing the number of SSCs did not significantly affect the accuracy of measurements.

Keywords: Cone-Beam Computed Tomography; Anatomic Landmarks; Artifacts; Alveolar Process

Introduction

Materials and Methods: This in vitro experimental study was conducted on 4 sheep hemi-mandibles. First, gutta-percha points were placed on the buccal and lingual surfaces of the alveolar ridge, and bone height and thickness were measured with a digital caliper (direct measurement). Then, three CBCT scans were obtained as follows: The first scan was performed without placing the SSCs, as the baseline image; the second scan was performed after placement of one SSC, and the third scan was performed in presence of 3 SSCs. Red wax was used for soft tissue simulation. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22 (alpha=0.05).

Results: The findings revealed no significant difference between the direct measurement and the baseline image in terms of measuring the bone height and thickness (P>0.05). The difference between the baseline and scan image measurements in presence of one SSC was not significant (P>0.05). Furthermore, the accuracy of CBCT images did not decrease after the placement of 3 SSCs.

Conclusion: The Presence of SSCs did not decrease the accuracy of linear measurement of alveolar bone height and thickness. Moreover, increasing the number of SSCs did not significantly affect the accuracy of measurements.

Keywords: Cone-Beam Computed Tomography; Anatomic Landmarks; Artifacts; Alveolar Process

Introduction

Dentistry relies on diagnostic imaging techniques for appropriate treatment planning for patients. Proper diagnosis and treatment planning are usually impossible without the help of imaging modalities. Panoramic radiography, periapical radiography, computed tomography, and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) are among the most frequently used imaging techniques in dentistry. An imaging technique may be selected depending on the importance of the required details [1,2]. Panoramic and intraoral imaging techniques have problems due to their two-dimensionality and superimposition of structures despite their advantages such as convenience, low radiation dose, and providing information about the shape and density of bone. The intrinsic limitations of two-dimensional images, such as magnification, distortion, and superimposition, lead to errors in examining the anatomical structures. Therefore, it is necessary to use new modalities with accurate estimations [3,4].

CBCT is a valuable imaging modality in dentistry suitable for analyzing the hard tissue of the maxillofacial region. This modality is popular for its high resolution and speed, as well as lower cost and radiation dose compared to computed tomography [5]. One major benefit of CBCT is that it enables linear measurement of anatomical structures, which is helpful for measurement of alveolar bone thickness and height prior to dental implant insertion [6,7].

On the other hand, the accuracy of CBCT images for alveolar bone measurements depends on various factors, including the voxel size, image analysis program, and presence/absence of soft tissue. Precise measurement of alveolar bone is crucial because of its effect on the outcome of periodontal and orthodontic treatments. Underestimation of alveolar bone height may lead to a misdiagnosis of bone loss [8].

An artifact is an image distortion that is not related to the evaluated area and causes a reduction in image quality and misinterpretation of the findings. Teeth with restorative treatments, root canal therapy, and metal posts are more likely to cause artifacts owing to higher absorption of low-energy photons compared to higher-energy photons in polychromatic X-rays [9]. A recent study suggested that presence of dental implants could affect the accuracy of CBCT images [10]. While CBCT is generally avoided in children due to radiation concerns, there are rare and complex cases where CBCT might be necessary, such as dentomaxillofacial anomalies, severe trauma affecting the bone structure, and pathological conditions [11, 12]. Stainless-steel crown (SSC) is the most commonly used restorative option to preserve the remaining tooth structure in severely damaged primary teeth. SSCs have the benefits of low cost, dependability, and durability, better than any other restorative material [13].

Since artifacts caused by dental restorations may lead to misinterpretation of CBCT findings, this study aimed to compare the accuracy of CBCT images in measuring the bone height and thickness before and after placing more than one SSC on teeth in dry sheep mandibles. The null hypothesis of the study was that presence of SSCs would have no significant effect on alveolar bone dimensions measured on CBCT scans.

Materials and Methods

CBCT is a valuable imaging modality in dentistry suitable for analyzing the hard tissue of the maxillofacial region. This modality is popular for its high resolution and speed, as well as lower cost and radiation dose compared to computed tomography [5]. One major benefit of CBCT is that it enables linear measurement of anatomical structures, which is helpful for measurement of alveolar bone thickness and height prior to dental implant insertion [6,7].

On the other hand, the accuracy of CBCT images for alveolar bone measurements depends on various factors, including the voxel size, image analysis program, and presence/absence of soft tissue. Precise measurement of alveolar bone is crucial because of its effect on the outcome of periodontal and orthodontic treatments. Underestimation of alveolar bone height may lead to a misdiagnosis of bone loss [8].

An artifact is an image distortion that is not related to the evaluated area and causes a reduction in image quality and misinterpretation of the findings. Teeth with restorative treatments, root canal therapy, and metal posts are more likely to cause artifacts owing to higher absorption of low-energy photons compared to higher-energy photons in polychromatic X-rays [9]. A recent study suggested that presence of dental implants could affect the accuracy of CBCT images [10]. While CBCT is generally avoided in children due to radiation concerns, there are rare and complex cases where CBCT might be necessary, such as dentomaxillofacial anomalies, severe trauma affecting the bone structure, and pathological conditions [11, 12]. Stainless-steel crown (SSC) is the most commonly used restorative option to preserve the remaining tooth structure in severely damaged primary teeth. SSCs have the benefits of low cost, dependability, and durability, better than any other restorative material [13].

Since artifacts caused by dental restorations may lead to misinterpretation of CBCT findings, this study aimed to compare the accuracy of CBCT images in measuring the bone height and thickness before and after placing more than one SSC on teeth in dry sheep mandibles. The null hypothesis of the study was that presence of SSCs would have no significant effect on alveolar bone dimensions measured on CBCT scans.

Materials and Methods

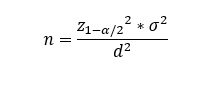

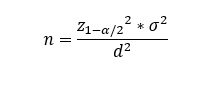

This in vitro experimental study was conducted on sheep mandibles as the study samples selected by convenience sampling. Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.MAZUMS.REC.1401.14935). The sample size was calculated according to a study by Ismail et al. [14], assuming a type I error (α) of 0.05, measurement error (d) of 0.4, and σ=0.64 using the following formula:

A total of 12 samples from 4 hemi-mandibles of sheep were included. Regions on the posterior part of the mandibles with at least three teeth in contact with each other were selected. Next, 1-mm holes were created in the buccal and lingual sides of the ridge, parallel to each other and at the same distance from the alveolar crest at the site of the middle tooth in all samples using high-speed round diamond bur. Gutta-percha points were placed in the holes as a radiopaque marker. The height and thickness (buccolingual width) of bone were measured using a digital caliper (Mitutoyo Series 500-144; Absolute, Suzano, Brazil) with an accuracy of 0.01 mm. The bone height was calculated by measuring the vertical distance from the edge of the crest to the gutta-percha point on the buccal side, as well as from the edge of the crest to the gutta-percha point on the lingual side. Moreover, the thickness was determined by measuring the distance between the buccal and lingual gutta-percha points. The mandible was covered with 1.5 cm of red wax to simulate the soft tissue [15], and a CBCT image (baseline) was obtained without any restoration on the teeth. Images were obtained using a CS9300 CBCT scanner (Carestream Dental LLC, Atlanta, GA, USA) at the Dental Faculty of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. The samples were exposed to radiation for 8 seconds under the following conditions: 10×10 cm field of view (FOV), 88 kVp tube potential, 6.3 mA tube current, and 180 µm voxel size (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CBCT scanning of the baseline samples

In the next step, the appropriate SSC was selected, and the tooth was reshaped with a taper round-end bur for occlusal adjustments. Proximal contacts were opened using a needle bur, without damaging the adjacent teeth. Finally, the corners and sharp edges were removed. The reshaping process was continued until the desired crown matched the tooth. Tooth preparation was performed on all surfaces such that the finish line was located near the crestal ridge. The SSC (D2; 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) was then cemented to the tooth. Another CBCT scan with the same parameters was obtained after cementation. Finally, mesially- and distally-positioned teeth relative to the middle tooth were prepared for SSCs with the same approach as mentioned above. D1 and E2 crowns were selected for mesial and distal teeth, respectively. As demonstrated in Figure 2, the third CBCT image was taken from the samples after placing the SSCs on the mesial and distal teeth, as well as the middle tooth.

Figure 2. SSCs placed on the teeth in a hemi-mandible of sheep

The scans were reviewed by two radiologists in a dark room on a 20-inch LCD monitor (1600×900 pixels; LG, South Korea). Reorientation of the reconstructed images was conducted while the occlusal plane was parallel to the horizon. Then, the panoramic view was reconstructed by drawing a curve through the center of each jaw in the axial section. In the next step, the bone height and thickness were measured using OnDemand 3D DentalTM software using the ruler tool in the toolbox section. On the cross-sectional view, the distance between the buccal alveolar crest and the gutta-percha point on the buccal side, as well as the distance between the lingual alveolar crest and the gutta-percha point on the lingual side, were calculated. Moreover, the thickness (buccolingual bone width) was measured based on the distance between the buccal and lingual gutta-percha points (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Measurement of bone thickness on the (a) axial, (b) cross-sectional, (c) panoramic, and (d) 3D views of CBCT images

The measurements obtained in direct measurement using the caliper, baseline measurements, and the measurements made on the CBCT scans were then compared. Two radiologists performed the measurements twice, with a one-month interval between the assessments, utilizing the ruler tool of OnDemand 3D DentalTM software. Diagnostic agreement was evaluated using sensitivity, specificity, area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve, and the intraclass correlation coefficient. In this study, descriptive indices, such as mean and standard deviation, were reported. For inferential analysis, the Friedman and Wilcoxon tests were used to compare the variables measured by different methods. SPSS version 22 was used for statistical calculations, and the significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

A total of 12 samples from 4 hemi-mandibles of sheep were included. Regions on the posterior part of the mandibles with at least three teeth in contact with each other were selected. Next, 1-mm holes were created in the buccal and lingual sides of the ridge, parallel to each other and at the same distance from the alveolar crest at the site of the middle tooth in all samples using high-speed round diamond bur. Gutta-percha points were placed in the holes as a radiopaque marker. The height and thickness (buccolingual width) of bone were measured using a digital caliper (Mitutoyo Series 500-144; Absolute, Suzano, Brazil) with an accuracy of 0.01 mm. The bone height was calculated by measuring the vertical distance from the edge of the crest to the gutta-percha point on the buccal side, as well as from the edge of the crest to the gutta-percha point on the lingual side. Moreover, the thickness was determined by measuring the distance between the buccal and lingual gutta-percha points. The mandible was covered with 1.5 cm of red wax to simulate the soft tissue [15], and a CBCT image (baseline) was obtained without any restoration on the teeth. Images were obtained using a CS9300 CBCT scanner (Carestream Dental LLC, Atlanta, GA, USA) at the Dental Faculty of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. The samples were exposed to radiation for 8 seconds under the following conditions: 10×10 cm field of view (FOV), 88 kVp tube potential, 6.3 mA tube current, and 180 µm voxel size (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CBCT scanning of the baseline samples

In the next step, the appropriate SSC was selected, and the tooth was reshaped with a taper round-end bur for occlusal adjustments. Proximal contacts were opened using a needle bur, without damaging the adjacent teeth. Finally, the corners and sharp edges were removed. The reshaping process was continued until the desired crown matched the tooth. Tooth preparation was performed on all surfaces such that the finish line was located near the crestal ridge. The SSC (D2; 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) was then cemented to the tooth. Another CBCT scan with the same parameters was obtained after cementation. Finally, mesially- and distally-positioned teeth relative to the middle tooth were prepared for SSCs with the same approach as mentioned above. D1 and E2 crowns were selected for mesial and distal teeth, respectively. As demonstrated in Figure 2, the third CBCT image was taken from the samples after placing the SSCs on the mesial and distal teeth, as well as the middle tooth.

Figure 2. SSCs placed on the teeth in a hemi-mandible of sheep

The scans were reviewed by two radiologists in a dark room on a 20-inch LCD monitor (1600×900 pixels; LG, South Korea). Reorientation of the reconstructed images was conducted while the occlusal plane was parallel to the horizon. Then, the panoramic view was reconstructed by drawing a curve through the center of each jaw in the axial section. In the next step, the bone height and thickness were measured using OnDemand 3D DentalTM software using the ruler tool in the toolbox section. On the cross-sectional view, the distance between the buccal alveolar crest and the gutta-percha point on the buccal side, as well as the distance between the lingual alveolar crest and the gutta-percha point on the lingual side, were calculated. Moreover, the thickness (buccolingual bone width) was measured based on the distance between the buccal and lingual gutta-percha points (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Measurement of bone thickness on the (a) axial, (b) cross-sectional, (c) panoramic, and (d) 3D views of CBCT images

The measurements obtained in direct measurement using the caliper, baseline measurements, and the measurements made on the CBCT scans were then compared. Two radiologists performed the measurements twice, with a one-month interval between the assessments, utilizing the ruler tool of OnDemand 3D DentalTM software. Diagnostic agreement was evaluated using sensitivity, specificity, area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve, and the intraclass correlation coefficient. In this study, descriptive indices, such as mean and standard deviation, were reported. For inferential analysis, the Friedman and Wilcoxon tests were used to compare the variables measured by different methods. SPSS version 22 was used for statistical calculations, and the significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

The intra-observer and inter-observer reliability values were found to be 0.89 and 0.85, respectively. The mean buccal and lingual bone height and buccolingual bone thickness are reported in Table 1. The mean buccal bone height ranged from 4.20±0.24 mm (third scan with 3 SSCs) to 4.51±0.28 mm (direct measurement), with a maximum mean difference of 0.30 mm observed between the methods. Quantitative analysis demonstrated no statistically significant differences (P>0.05) between direct caliper measurements and CBCT scans across all experimental conditions. Similarly, lingual bone height varied from 4.47±0.05 mm (direct) to 5.05±0.82 mm (third scan), yielding a maximum mean difference of 0.58 mm. Buccolingual bone thickness remained consistent, with direct measurements averaging 11.50±0.22 mm compared to CBCT ranges of 11.20 to 11.32 mm across scans (maximum mean difference: 0.30 mm). As demonstrated in Table 2, the differences in the buccal and lingual bone height, as well as bone thickness measured on CBCT scans with the direct measurements were not statistically significant (P>0.05). Critically, all differences between the direct and CBCT measurements fell below the 1 mm threshold for clinical significance. The intraclass correlation coefficients further confirmed strong agreement between methods, with values of 0.77 (P=0.039) for buccal bone height, 0.87 (P=0.008) for lingual bone height, and 0.96 (P=0.001) for bone thickness. Thus, presence of one single or multiple SSCs did not compromise the accuracy of CBCT-based alveolar bone measurements (Table 3).

Table 1. Mean and standard deviation of direct and CBCT measurements (in millimeters)

Table 2. Mean difference and standard deviation in buccal and lingual bone height, and bone thickness measured on CBCT scans in comparison with the direct technique

Table 3. Intraclass correlation coefficient between the methods

Discussion

Table 1. Mean and standard deviation of direct and CBCT measurements (in millimeters)

Table 2. Mean difference and standard deviation in buccal and lingual bone height, and bone thickness measured on CBCT scans in comparison with the direct technique

Table 3. Intraclass correlation coefficient between the methods

Discussion

The findings of the current study suggested that the mean difference between the direct caliper measurements and baseline CBCT measurements was not statistically significant; thus, the null hypothesis of the study was accepted. The results obtained from this study were in line with some other investigations conducted in this field [14,16].

SSCs are used for severely carious primary teeth [13]. While CBCT is rarely indicated in children due to radiation concerns, it becomes indispensable in complex cases such as trauma or pathological lesions [12]. The current study suggests that when CBCT is indicated, SSCs do not impede accurate bone assessments, empowering clinicians to plan surgeries or evaluate pathologies without artifact-induced uncertainty. Unlike high-density alloys, which cause beam-hardening artifacts that distort CBCT measurements [17], SSCs appear to be minimally disruptive. This may be attributed to their lower metal density and homogeneous composition, which reduces photon starvation effects. These results align with those of Ismail et al. [14], who reported no measurement inaccuracies even with eight SSCs in porcine mandibles. However, the current findings contradicted those of Fakhar et al. [18] who reported metal-induced underestimations with nickel-chromium crowns. This controversy suggests that material properties, not mere presence of metal, dictates the artifact severity.

Absence of significant differences in the triple SSC group demonstrates that adjacent crowns do not cause measurement errors. This addresses a critical gap, as multiple restorations are common in pediatric rehabilitation yet poorly studied in CBCT literature. On the other hand, Adarsh et al. [19] compared CBCT measurements with conventional imaging modalities for tooth length measurements and reported that linear measurements on CBCT images in the craniofacial region were accurate and reliable. Another study performed measurements on 30 teeth restored with metal-ceramic and full-ceramic veneers and found no significant difference between measurements with manual and three-dimensional methods [20]. Linear and volumetric measurements on the condyles of human cadavers have shown that CBCT is a reliable method and does not have a significant difference with the measurements made with a digital caliper [16]. Additionally, linear measurements of the human skull made on CBCT scans with large and small FOVs did not have a significant difference with direct measurements 21]. Ganguly et al. [22] assessed linear measurements of edentulous regions in the maxilla and mandible on four human cadavers using different FOVs and voxel sizes and found no significant difference between different CBCT settings or direct measurement methods. On the other hand, in another study, CBCT measurements of the buccal bone thickness on human cadavers were significantly smaller than direct measurements and resulted in underestimations [23]. Features of CBCT scanners can affect the accuracy of measurements, which include non-operator-dependent variables such as filtration, source-to-object distance, object-to-sensor distance, reconstruction algorithms used, or the design of different limiting devices [24]. This controversy can be attributed to the difference in study design as well as the exposure conditions such as FOV, voxel size, irradiation time, tube potential, and tube current. Additionally, Lira de Farias Freitas et al. [17] calculated the dimensions of nickel-chromium and silver-palladium posts on CBCT scans and reported that high atomic number alloys decrease the accuracy of CBCT measurements. The reason for this difference can be attributed to the beam hardening artifact created by gold alloys, which has been increasingly observed in metal posts. In contrast with the present investigation, Moshfeghi et al. [25] discovered a significant difference between the CBCT and direct measurements made on sheep dry mandible; however, the difference was less than 1 mm. Several studies have considered a 1-mm difference as the clinical error threshold [24, 26]. These conflicting results can be explained by the difference in exposure conditions. Studies that simulate soft tissue conditions provide more accurate results since the settings are similar to clinical conditions. Thus, some investigations use samples with soft tissue [14] and some others use the water immersion technique to simulate the soft tissue [27, 28]. In line with other investigations [15, 21], the present study used 1.5 cm of red wax to simulate the soft tissue. The artifact created by metal objects results from beam hardening, which occurs in almost all computed tomography and CBCT imaging systems. In some cases, the artifact is so severe that it reduces the quality of the image or even distorts the image [29]. The current study observed that presence of SSC on the target tooth and adjacent teeth did not reduce the accuracy of linear measurements made on CBCT images.

This study had some limitations. The use of sheep mandibles may not fully replicate human anatomical complexity, and the small sample size limits broad generalizability of the findings. Future research should validate these results in human specimens or clinical cohorts, incorporating diverse CBCT systems and voxel resolutions. Assessing other high-density materials and advanced artifact-reduction algorithms would strengthen the clinical applicability of the results.

Conclusion

SSCs are used for severely carious primary teeth [13]. While CBCT is rarely indicated in children due to radiation concerns, it becomes indispensable in complex cases such as trauma or pathological lesions [12]. The current study suggests that when CBCT is indicated, SSCs do not impede accurate bone assessments, empowering clinicians to plan surgeries or evaluate pathologies without artifact-induced uncertainty. Unlike high-density alloys, which cause beam-hardening artifacts that distort CBCT measurements [17], SSCs appear to be minimally disruptive. This may be attributed to their lower metal density and homogeneous composition, which reduces photon starvation effects. These results align with those of Ismail et al. [14], who reported no measurement inaccuracies even with eight SSCs in porcine mandibles. However, the current findings contradicted those of Fakhar et al. [18] who reported metal-induced underestimations with nickel-chromium crowns. This controversy suggests that material properties, not mere presence of metal, dictates the artifact severity.

Absence of significant differences in the triple SSC group demonstrates that adjacent crowns do not cause measurement errors. This addresses a critical gap, as multiple restorations are common in pediatric rehabilitation yet poorly studied in CBCT literature. On the other hand, Adarsh et al. [19] compared CBCT measurements with conventional imaging modalities for tooth length measurements and reported that linear measurements on CBCT images in the craniofacial region were accurate and reliable. Another study performed measurements on 30 teeth restored with metal-ceramic and full-ceramic veneers and found no significant difference between measurements with manual and three-dimensional methods [20]. Linear and volumetric measurements on the condyles of human cadavers have shown that CBCT is a reliable method and does not have a significant difference with the measurements made with a digital caliper [16]. Additionally, linear measurements of the human skull made on CBCT scans with large and small FOVs did not have a significant difference with direct measurements 21]. Ganguly et al. [22] assessed linear measurements of edentulous regions in the maxilla and mandible on four human cadavers using different FOVs and voxel sizes and found no significant difference between different CBCT settings or direct measurement methods. On the other hand, in another study, CBCT measurements of the buccal bone thickness on human cadavers were significantly smaller than direct measurements and resulted in underestimations [23]. Features of CBCT scanners can affect the accuracy of measurements, which include non-operator-dependent variables such as filtration, source-to-object distance, object-to-sensor distance, reconstruction algorithms used, or the design of different limiting devices [24]. This controversy can be attributed to the difference in study design as well as the exposure conditions such as FOV, voxel size, irradiation time, tube potential, and tube current. Additionally, Lira de Farias Freitas et al. [17] calculated the dimensions of nickel-chromium and silver-palladium posts on CBCT scans and reported that high atomic number alloys decrease the accuracy of CBCT measurements. The reason for this difference can be attributed to the beam hardening artifact created by gold alloys, which has been increasingly observed in metal posts. In contrast with the present investigation, Moshfeghi et al. [25] discovered a significant difference between the CBCT and direct measurements made on sheep dry mandible; however, the difference was less than 1 mm. Several studies have considered a 1-mm difference as the clinical error threshold [24, 26]. These conflicting results can be explained by the difference in exposure conditions. Studies that simulate soft tissue conditions provide more accurate results since the settings are similar to clinical conditions. Thus, some investigations use samples with soft tissue [14] and some others use the water immersion technique to simulate the soft tissue [27, 28]. In line with other investigations [15, 21], the present study used 1.5 cm of red wax to simulate the soft tissue. The artifact created by metal objects results from beam hardening, which occurs in almost all computed tomography and CBCT imaging systems. In some cases, the artifact is so severe that it reduces the quality of the image or even distorts the image [29]. The current study observed that presence of SSC on the target tooth and adjacent teeth did not reduce the accuracy of linear measurements made on CBCT images.

This study had some limitations. The use of sheep mandibles may not fully replicate human anatomical complexity, and the small sample size limits broad generalizability of the findings. Future research should validate these results in human specimens or clinical cohorts, incorporating diverse CBCT systems and voxel resolutions. Assessing other high-density materials and advanced artifact-reduction algorithms would strengthen the clinical applicability of the results.

Conclusion

The current findings indicated that the CBCT imaging technique had appropriate accuracy in presence of SSCs, and no significant difference was observed between direct and baseline CBCT measurements. The artifact caused by SSCs did not cause a significant change in CBCT measurements compared to the direct measurements. Furthermore, increasing the number of crowns near the desired location did not significantly affect the measurement accuracy, and did not cause overestimation or underestimation of the alveolar bone height.

Type of Study: Original article |

Subject:

Radiology

References

1. Sharma R, Muralidharan CG, Verma M, Pannu S, Patrikar S. MRI changes in the temporomandibular joint after mandibular advancement. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020 May;78(5):806-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.joms.2019.12.028] [PMID]

2. Khodabakhshian A, Mollaei M, Alimohammadi M, Ghobadi F, Hosseinnataj A, Gholampour A. Assessing the variations of the depth and angle of the submandibular gland fossa and the mandibular canal using cone beam computed tomography (CBCT): Submandibular gland fossa assessment using CBCT. Regen. reconstr. restor. 2024;9.

3. Rodriguez AB, Ayyildiz BG, Ayyildiz H, Narvekar A, Elnagar MH, Schmerman M, et al. CBCT validation study on intraclass correlation for linear measurements in peri-implantitis: an observational study. J Oral Maxillofac Res. 2025 Mar;16(1):e4. [DOI:10.5037/jomr.2025.16104] [PMID] []

4. Shalabi MM, Darwich KMA, Kheshfeh MN, Hajeer MY. Accuracy of 3D virtual surgical planning compared to the traditional two-dimensional method in orthognathic surgery: A literature review. Cureus. 2024 Nov;16(11):e73477. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.73477]

5. Dadgar S, Aryana M, Khorankeh M, Mollaei M, Alizadeh-Navaei R, Sobouti F. Morphological evaluation of maxillary arch in unilateral buccally and palatally impacted canines: a cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT)-based study in Northern Iran. Pol J Radiol. 2024 Jun;89:e316-23. [DOI:10.5114/pjr/188686] [PMID] []

6. Hali H, Salehi Sarookollaei M, Alimohammadi M, Hosseinnataj A, Khalili B, Mollaei M. Localization of impacted maxillary canines and root resorption of neighboring incisors using cone beam computed tomography in people aged 12-20 in Sari. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2023 Nov;33(1):226-33.

7. Gholampour A, Mollaei M, Alimohammadi M, Yaghoubi S, Hosseinnataj A, Mollazadeh Z. Accuracy of bone height and thickness measurements in cone beam computed tomography in the presence of porcelain fused to metal (PFM) crowns. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2024 Oct;36(4):397-401. [DOI:10.4103/jiaomr.jiaomr_203_24]

8. Li Y, Deng S, Mei L, Li J, Qi M, Su S, et al. Accuracy of alveolar bone height and thickness measurements in cone beam computed tomography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2019 Dec;128(6):667-79. [DOI:10.1016/j.oooo.2019.05.010] [PMID]

9. Fox A, Basrani B, Kishen A, Lam EWN. A novel method for characterizing beam hardening artifacts in cone-beam computed tomographic images. J Endod. 2018 May;44(5):869-74. [DOI:10.1016/j.joen.2018.02.005] [PMID]

10. Gholampour A, Mollaei M, Ehsani H, Ghobadi F, Hosseinnataj A, Yazdani M. Evaluation of the accuracy of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) in the detection of peri-implant fenestration. BMC Oral Health. 2024 Aug;24(1):922. [DOI:10.1186/s12903-024-04674-z] [PMID] []

11. Ismayılov R, Özgür B. Indications and use of cone beam computed tomography in children and young individuals in a university-based dental hospital. BMC Oral Health. 2023 Dec;23(1):1033. [DOI:10.1186/s12903-023-03784-4] [PMID] []

12. İşman Ö, Yılmaz HH, Aktan AM, Yilmaz B. Indications for cone beam computed tomography in children and young patients in a Turkish subpopulation. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2017 May;27(3):183-90. [DOI:10.1111/ipd.12250] [PMID]

13. Mathew MG, Roopa KB, Soni AJ, Khan MM, Kauser A. Evaluation of clinical success, parental and child satisfaction of stainless steel crowns and zirconia crowns in primary molars. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020 Mar;9(3):1418-23. [DOI:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1006_19] [PMID] []

14. Ismail A, Lakschevitz F, MacDonald D, Ford NL. Measurement accuracy in cone beam computed tomography in the presence of metal artifact. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2022 Jan-Feb;37(1):143-52. [DOI:10.11607/jomi.9079] [PMID]

15. Vadiati Saberi B, Khosravifard N, Ghandari F, Hadinezhad A. Detection of peri-implant bone defects using cone-beam computed tomography and digital periapical radiography with parallel and oblique projection. Imaging Sci Dent. 2019 Dec;49(4):265-72. [DOI:10.5624/isd.2019.49.4.265] [PMID] []

16. García-Sanz V, Bellot-Arcís C, Hernández V, Serrano-Sánchez P, Guarinos J, Paredes-Gallardo V. Accuracy and reliability of cone-beam computed tomography for linear and volumetric mandibular condyle measurements. A human cadaver study. Sci Rep. 2017 Sep;7(1):11993. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-12100-4] [PMID] []

17. Lira de Farias Freitas AP, Cavalcanti YW, Costa FCM, Peixoto LR, Maia AMA, Rovaris K, et al. Assessment of artefacts produced by metal posts on CBCT images. Int Endod J. 2019 Feb;52(2):223-36. [DOI:10.1111/iej.12999] [PMID]

18. Fakhar HB, Rashtchian R, Parvin M. Effect of dental implant metal artifacts on accuracy of linear measurements by two cone-beam computed tomography systems before and after crown restoration. J Dent (Tehran). 2017 Nov;14(6):329-36.

19. Adarsh K, Sharma P, Juneja A. Accuracy and reliability of tooth length measurements on conventional and CBCT images: An in vitro comparative study. J Orthod Sci. 2018 Sep;7:17. [DOI:10.4103/jos.JOS_21_18] [PMID] []

20. Doriguêtto PVT, de Almeida D, de Lima CO, Lopes RT, Devito KL. Assessment of marginal gaps and image quality of crowns made of two different restorative materials: An in vitro study using CBCT images. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2022 Fall;16(4):243-50. [DOI:10.34172/joddd.2022.039] [PMID] []

21. Mehdizadeh M, Erfani A, Soltani P. Comparison of the accuracy of linear measurements in CBCT images with different field of views. Clin Lab Res Dent. 2022 Apr 6;1-4. [DOI:10.11606/issn.2357-8041.clrd.2022.194059]

22. Ganguly R, Ramesh A, Pagni S. The accuracy of linear measurements of maxillary and mandibular edentulous sites in cone-beam computed tomography images with different fields of view and voxel sizes under simulated clinical conditions. Imaging Sci Dent. 2016 Jun;46(2):93-101. [DOI:10.5624/isd.2016.46.2.93] [PMID] []

23. Vanderstuyft T, Tarce M, Sanaan B, Jacobs R, de Faria Vasconcelos K, Quirynen M. Inaccuracy of buccal bone thickness estimation on cone-beam CT due to implant blooming: An ex-vivo study. J Clin Periodontol. 2019 Nov;46(11):1134-43. [DOI:10.1111/jcpe.13183] [PMID]

24. Fokas G, Vaughn VM, Scarfe WC, Bornstein MM. Accuracy of linear measurements on CBCT images related to presurgical implant treatment planning: A systematic review. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2018 Oct;29 Suppl 16:393-415. [DOI:10.1111/clr.13142] [PMID]

25. Moshfeghi M, Amintavakoli M, Ghaznavi D, Ghaznavi A. Effect of slice thickness on the accuracy of linear measurements made on cone beam computed tomography images (invitro). J Dent Sch. 2016 Jun;34(2):100-8.

26. Haas LF, Zimmermann GS, De Luca Canto G, Flores-Mir C, Corrêa M. Precision of cone beam CT to assess periodontal bone defects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2018 Feb;47(2):20170084. [DOI:10.1259/dmfr.20170084] [PMID] []

27. Ghaznavi A, Ghaznavi D, Valizadeh S, Vasegh Z, Al-Shuhayeb M. Accuracy of linear measurements made on cone beam computed tomography scans at different magnifications. J contemp med sci. 2019 Sep;5(5). [DOI:10.22317/jcms.10201907]

28. Sheikhi M, Gholami SA, Ghazizadeh M. Accuracy of CBCT linear measurements to determine the height of alveolar crest to the mental foramen. Avicenna J Dent Res. 2021 Mar;13(1):1-5. [DOI:10.34172/ajdr.2021.01]

29. Yang FQ, Zhang DH, Huang KD, Yang YF, Liao JM. Image artifacts and noise reduction algorithm for cone-beam computed tomography with low-signal projections. J Xray Sci Technol. 2018 Apr;26(2):227-40. [DOI:10.3233/XST-17285] [PMID]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |