Volume 10, Issue 4 (12-2025)

J Res Dent Maxillofac Sci 2025, 10(4): 338-345 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.SSU.DENTISTRY.REC.1402.077

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Barzegar M, Bemani A, Pouyafard A. Serum Concentrations of Calcium and 25-Hydroxy-vitamin D, and Calcium Intake in Iranian Patients with Self-Reported Sleep Bruxism: A Case-Control Study. J Res Dent Maxillofac Sci 2025; 10 (4) :338-345

URL: http://jrdms.dentaliau.ac.ir/article-1-923-en.html

URL: http://jrdms.dentaliau.ac.ir/article-1-923-en.html

1- Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, School of Dentistry, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran

2- School of Dentistry, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran

3- Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine, School of Dentistry, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran ,a.pouyafard@gmail.com

2- School of Dentistry, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran

3- Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine, School of Dentistry, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran ,

Full-Text [PDF 336 kb]

(14 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (22 Views)

Table 4. Correlation coefficients for the association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, calcium level, daily calcium intake, and monthly income

Additionally, there appears to be a connection between low vitamin D levels and various sleep problems, including bruxism [9,19-21]. These findings align with the results of the present study. The results of this study indicated a significant and direct correlation between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, serum calcium levels, and daily calcium intake. It means that individuals with higher serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels also had significantly higher serum calcium levels and daily calcium intake.

Various studies have noted that low levels of vitamin D can disrupt calcium homeostasis and impact neuronal excitability [22-25]. Additionally, since vitamin D plays a crucial role in maintaining calcium balance, insufficient levels of vitamin D lead to a reduction in serum calcium levels (hypocalcemia) and muscle spasms and cramps, which aligns with the findings of the current study [22-25].

Anxiety, stress, and psychological factors have been identified as significant contributors to bruxism in numerous studies. Alkhatatbeh et al. [15] reported that individuals with bruxism exhibited higher levels of stress and anxiety compared to those without this condition. Additionally, a study by Allaf and Abdul-Hak [14] demonstrated that increased severity of vitamin D deficiency was associated with worsening of bruxism.

In the present study, however, an analysis of self-reported results from the Beck questionnaire revealed no significant differences in stress and anxiety levels between the control and case groups. These findings contradict the results of previous studies [15,23]. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in how stress levels are measured, variations in the statistical populations studied, and the smaller sample size of the current study.

This study suggested that individuals with higher monthly incomes tend to have significantly higher serum calcium and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. Two previous studies suggested that this disorder is more common among children from higher socioeconomic classes [26,27]. However, the results of the present study are inconsistent with earlier findings in this regard. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in the socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds of the target groups across various studies and countries. Socioeconomic and cultural characteristics may be linked to the prevalence of sleep bruxism [28].

This study had some limitations; for instance, the diagnosis of sleep bruxism was not confirmed through polysomnography, as this method is expensive, time-consuming, and unavailable at the study location. Thus, bruxism was assessed by using a validated questionnaire. This study can encourage others to investigate the potential cause-and-effect relationship between sleep bruxism, vitamin D deficiency, and low calcium levels. Additionally, further research is necessary to determine whether correcting vitamin D deficiency and increasing dietary calcium intake can alleviate the symptoms of sleep bruxism and provide practical suggestions for the treatment of this disorder.

Conclusion

Full-Text: (5 Views)

Abstract

Background and Aim: Recent evidence suggests a link between sleep bruxism and vitamin D deficiency. This study aimed to investigate the serum concentrations of calcium and 25-dihydroxyvitamin D, as well as calcium intake in patients with self-reported sleep bruxism versus healthy controls.

Materials and Methods: This case-control study evaluated 32 participants between 18 and 44 years old in each of the case and control groups, who were selected among patients referring to Yazd Dental School. The severity of bruxism was assessed using a questionnaire related to the classification of bruxism, and clinical examinations were performed to assess abnormal tooth wear. The daily calcium intake was estimated based on the frequency and amount of consumption of milk, yogurt, and cheese. The serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D was measured using the relevant kit, and the serum calcium level was measured by spectrophotometry. Data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test, Independent sample t-test, Fisher’s exact test, and Spearman’s correlation coefficient (alpha=0.05).

Results: The mean daily calcium intake in the case group was significantly lower than that in the control group (P<0.001). However, the mean serum calcium levels did not differ significantly between the case and control groups (P>0.05). The mean serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the case group was significantly lower than that in the control group (P<0.001).

Conclusion: According to the present results, the mean serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in bruxers was significantly lower than that in healthy controls. Bruxism was significantly associated with vitamin D deficiency in our study population.

Introduction

Materials and Methods: This case-control study evaluated 32 participants between 18 and 44 years old in each of the case and control groups, who were selected among patients referring to Yazd Dental School. The severity of bruxism was assessed using a questionnaire related to the classification of bruxism, and clinical examinations were performed to assess abnormal tooth wear. The daily calcium intake was estimated based on the frequency and amount of consumption of milk, yogurt, and cheese. The serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D was measured using the relevant kit, and the serum calcium level was measured by spectrophotometry. Data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test, Independent sample t-test, Fisher’s exact test, and Spearman’s correlation coefficient (alpha=0.05).

Results: The mean daily calcium intake in the case group was significantly lower than that in the control group (P<0.001). However, the mean serum calcium levels did not differ significantly between the case and control groups (P>0.05). The mean serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the case group was significantly lower than that in the control group (P<0.001).

Conclusion: According to the present results, the mean serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in bruxers was significantly lower than that in healthy controls. Bruxism was significantly associated with vitamin D deficiency in our study population.

Introduction

Bruxism is characterized by repetitive and involuntary clenching of the teeth, which can occur both during sleep and while awake. Although it is not life-threatening, it can significantly impair the quality of life. The consequences of bruxism can be extensive, leading to issues such as temporomandibular joint pain and dysfunction, headache, neck pain, tooth hypersensitivity, tooth wear, and muscle spasm [1]. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recognizes bruxism as a movement disorder associated with sleep [2].

There is emerging evidence suggesting that vitamin D may be essential for brainstem regulation during sleep, given the presence of vitamin D receptors in the brain regions that control sleep cycles. Additionally, vitamin D deficiency is frequently observed in individuals with sleep disorders and is considered a contributing factor to sleep disturbances. This points to a possible link between bruxism, especially sleep-related bruxism, and vitamin D deficiency [3,4].

Furthermore, deficiencies in essential minerals such as calcium and magnesium may also play a role in the development of bruxism, as they are vital for nervous system regulation and muscle function [5,6]. Adequate vitamin D levels are necessary for maintaining proper calcium balance within the body. Optimal levels of both vitamin D and calcium are crucial for normal muscle function, including the muscles involved in jaw contraction [7]. Inadequate calcium levels may ensue from insufficient vitamin D intake, potentially leading to muscle weakness, spasms, and tremors, thereby indirectly contributing to bruxism [8].

Given that bruxism is among the most prevalent destructive dental disorders, identifying its influencing factors is vital to prevent its potential complications [1]. Nonetheless, there is currently a scarcity of reliable clinical research in this area. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the serum concentrations of calcium and 25-dihydroxyvitamin D, as well as calcium intake in patients with self-reported sleep bruxism versus healthy controls in Yazd city, Iran.

Materials and Methods

There is emerging evidence suggesting that vitamin D may be essential for brainstem regulation during sleep, given the presence of vitamin D receptors in the brain regions that control sleep cycles. Additionally, vitamin D deficiency is frequently observed in individuals with sleep disorders and is considered a contributing factor to sleep disturbances. This points to a possible link between bruxism, especially sleep-related bruxism, and vitamin D deficiency [3,4].

Furthermore, deficiencies in essential minerals such as calcium and magnesium may also play a role in the development of bruxism, as they are vital for nervous system regulation and muscle function [5,6]. Adequate vitamin D levels are necessary for maintaining proper calcium balance within the body. Optimal levels of both vitamin D and calcium are crucial for normal muscle function, including the muscles involved in jaw contraction [7]. Inadequate calcium levels may ensue from insufficient vitamin D intake, potentially leading to muscle weakness, spasms, and tremors, thereby indirectly contributing to bruxism [8].

Given that bruxism is among the most prevalent destructive dental disorders, identifying its influencing factors is vital to prevent its potential complications [1]. Nonetheless, there is currently a scarcity of reliable clinical research in this area. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the serum concentrations of calcium and 25-dihydroxyvitamin D, as well as calcium intake in patients with self-reported sleep bruxism versus healthy controls in Yazd city, Iran.

Materials and Methods

This case-control study included 32 individuals in the bruxism group and 32 in the control group. The participants were selected through convenience sampling among patients referred to Yazd Dental School. The two groups were matched in terms of age and gender. The control group consisted of patients who exhibited no symptoms of bruxism or sleep disturbances and showed no signs of tooth wear during clinical examinations. The study was conducted at the Oral Medicine Department of the School of Dentistry, Yazd University of Medical Sciences, between 2023 and 2024. The university ethics committee approved the study protocol (IR.SSU.DENTISTRY.REC.1402.077).

The inclusion criteria were age between 18 and 44 years, presence of bruxism for the test group, determined through a questionnaire for bruxism classification, and clinical examination of abnormal tooth attrition. For the control group, the selected individuals did not exhibit symptoms of bruxism, headaches in the temporal region, musculoskeletal pain, muscle fatigue, or sleep problems. The exclusion criteria included history of taking medications that could interfere with calcium and vitamin D metabolism (such as glucocorticoids, anticonvulsants, antiretrovirals, diuretics, amphetamines, methamphetamines, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, antipsychotics, and antihistamines), conditions affecting the vitamin D metabolism, such as chronic kidney disease or liver disease, nerve-damaging conditions like diabetes mellitus or brain stroke [9], history of migraine, intake of calcium and vitamin D supplements in the past 2 months, history of smoking, and habitual coffee consumption [10,11]. Furthermore, participants who had fixed or removable dentures with more than three units, or those exhibiting severe malocclusion, were not eligible for study inclusion [12,13].

The researcher used a pre-designed checklist to record demographic information of patients, which also had questions to confirm each participant's bruxism status. This checklist was based on the criteria established by Allaf and Abdul-Hak [14], which included six yes-or-no questions. Individuals were classified as having bruxism if they answered "yes" to at least two of six items. The severity of bruxism was evaluated using a classification questionnaire consisting of 25 questions, with severity levels defined as follows: mild (3-5), moderate (6-10), severe (11-15), and very severe (16-25). Clinical examinations were also conducted to assess abnormal tooth wear. After obtaining written informed consent from the participants, a laboratory technician collected venous blood samples to evaluate serum calcium and vitamin D levels. The level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D was measured using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay kit (Ideal Future Diagnostics Company, Iran) while serum calcium levels were measured by spectrophotometry with a quantitative calcium detection kit (Pars Azmoun Company, Iran). The frequency and amount of milk, yogurt, and cheese consumption were also assessed to estimate daily calcium intake in milligrams (mg). Participants reported the frequency and amount of consumption of these dairy products as zero, one, two, or more than three servings per day. One serving was defined as follows: one cup (240 mL) of yogurt or milk provides 300 mg of calcium; one ounce of cream cheese contains 20 mg of calcium; one ounce of cheddar cheese provides 162 mg of calcium, and two tablespoons (equivalent to 1 oz) of labneh cheese contains 100 mg of calcium. Such details were recorded in the patient information checklist [15]. Additionally, the Beck Anxiety Inventory self-reported questionnaire, which has been validated and confirmed for reliability in Persian language, was used to assess the patients' anxiety level [16].

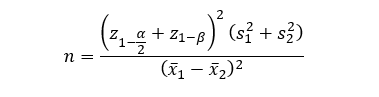

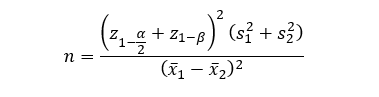

The sample size was calculated to be 32 in each of the two groups based on a previous study [15], assuming a significance level of 5% and a power of 80%, and considering the estimated standard deviation in the case and control groups obtained from a previous study [15] as S2=15.18, and S1=17.04. To achieve a significant difference of at least 11.5 units in the mean vitamin D level between the two groups, 32 participants were required in each group. The sample size was calculated using PASS 2021 software.

It should be noted that full explanations regarding the study objectives and methods were provided to the participants, and their consent to participate in the study was obtained. To compare qualitative data between the two groups, the Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were utilized. For quantitative data, the independent sample t-test was employed for normally distributed data, while the Mann-Whitney test was used for quantitative data without a normal distribution. Multiple binary logistic regression was applied to analyze the association between bruxism and serum calcium and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 27 (SPSS Inc., IL, USA) with a significance level set at 0.05.

Results

The inclusion criteria were age between 18 and 44 years, presence of bruxism for the test group, determined through a questionnaire for bruxism classification, and clinical examination of abnormal tooth attrition. For the control group, the selected individuals did not exhibit symptoms of bruxism, headaches in the temporal region, musculoskeletal pain, muscle fatigue, or sleep problems. The exclusion criteria included history of taking medications that could interfere with calcium and vitamin D metabolism (such as glucocorticoids, anticonvulsants, antiretrovirals, diuretics, amphetamines, methamphetamines, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, antipsychotics, and antihistamines), conditions affecting the vitamin D metabolism, such as chronic kidney disease or liver disease, nerve-damaging conditions like diabetes mellitus or brain stroke [9], history of migraine, intake of calcium and vitamin D supplements in the past 2 months, history of smoking, and habitual coffee consumption [10,11]. Furthermore, participants who had fixed or removable dentures with more than three units, or those exhibiting severe malocclusion, were not eligible for study inclusion [12,13].

The researcher used a pre-designed checklist to record demographic information of patients, which also had questions to confirm each participant's bruxism status. This checklist was based on the criteria established by Allaf and Abdul-Hak [14], which included six yes-or-no questions. Individuals were classified as having bruxism if they answered "yes" to at least two of six items. The severity of bruxism was evaluated using a classification questionnaire consisting of 25 questions, with severity levels defined as follows: mild (3-5), moderate (6-10), severe (11-15), and very severe (16-25). Clinical examinations were also conducted to assess abnormal tooth wear. After obtaining written informed consent from the participants, a laboratory technician collected venous blood samples to evaluate serum calcium and vitamin D levels. The level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D was measured using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay kit (Ideal Future Diagnostics Company, Iran) while serum calcium levels were measured by spectrophotometry with a quantitative calcium detection kit (Pars Azmoun Company, Iran). The frequency and amount of milk, yogurt, and cheese consumption were also assessed to estimate daily calcium intake in milligrams (mg). Participants reported the frequency and amount of consumption of these dairy products as zero, one, two, or more than three servings per day. One serving was defined as follows: one cup (240 mL) of yogurt or milk provides 300 mg of calcium; one ounce of cream cheese contains 20 mg of calcium; one ounce of cheddar cheese provides 162 mg of calcium, and two tablespoons (equivalent to 1 oz) of labneh cheese contains 100 mg of calcium. Such details were recorded in the patient information checklist [15]. Additionally, the Beck Anxiety Inventory self-reported questionnaire, which has been validated and confirmed for reliability in Persian language, was used to assess the patients' anxiety level [16].

The sample size was calculated to be 32 in each of the two groups based on a previous study [15], assuming a significance level of 5% and a power of 80%, and considering the estimated standard deviation in the case and control groups obtained from a previous study [15] as S2=15.18, and S1=17.04. To achieve a significant difference of at least 11.5 units in the mean vitamin D level between the two groups, 32 participants were required in each group. The sample size was calculated using PASS 2021 software.

It should be noted that full explanations regarding the study objectives and methods were provided to the participants, and their consent to participate in the study was obtained. To compare qualitative data between the two groups, the Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were utilized. For quantitative data, the independent sample t-test was employed for normally distributed data, while the Mann-Whitney test was used for quantitative data without a normal distribution. Multiple binary logistic regression was applied to analyze the association between bruxism and serum calcium and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 27 (SPSS Inc., IL, USA) with a significance level set at 0.05.

Results

The study sample consisted of 32 patients with bruxism (the case group) and 32 control participants, including 28 males and 36 females. In both groups, there were 14 males (59%) and 18 females (50%), indicating no significant difference in gender distribution, as demonstrated by the Chi-square test (P=0.910). The mean age of all patients was 24.81±6.20 years, with a range of 18 to 44 years. The mean age was 25.78±7.72 years in the case group, and 23.84±4.06 years in the control group. There was no significant difference in the mean age between the two groups, as shown by the t-test (P=0.872). No significant difference was found between the two groups regarding educational level (P=0.870) and average monthly income (P=0.095). Figure 1 shows the frequency distribution of different severities of bruxism. As shown, 50% of patients had moderate bruxism.

Figure 1. Frequency distribution of bruxism severity in the case group

Of 33 individuals who reported no stress, 14 (41.2%) belonged to the case group, and 20 (58.8%) belonged to the control group. Of 25 individuals experiencing mild stress, 15 (60%) were in the case group, and 10 (40%) were in the control group. Of the 5 individuals with moderate stress, 3 (60%) belonged to the case and 2 (40%) to the control group. No significant difference was found between the two groups in the level of stress and anxiety (P=0.307).

Table 1 shows the mean daily calcium intake in the two groups. As shown, the mean daily calcium intake in the case group was significantly lower than that in the control group (P<0.001).

Table 2 shows the mean serum calcium level in the two groups. The two groups had no significant difference in this regard (P=0.139).

Table 1. Comparison of the mean daily calcium intake (mg/day) between the two groups

Table 2. Comparison of the mean serum calcium level (mg/dL) between the two groups

Furthermore, the mean serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level in the case group was significantly lower than that in the control group (Table 3, P< 0.001).

Table 3. Comparison of the mean serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level (Nmol/L) between the two groups

Figure 1. Frequency distribution of bruxism severity in the case group

Of 33 individuals who reported no stress, 14 (41.2%) belonged to the case group, and 20 (58.8%) belonged to the control group. Of 25 individuals experiencing mild stress, 15 (60%) were in the case group, and 10 (40%) were in the control group. Of the 5 individuals with moderate stress, 3 (60%) belonged to the case and 2 (40%) to the control group. No significant difference was found between the two groups in the level of stress and anxiety (P=0.307).

Table 1 shows the mean daily calcium intake in the two groups. As shown, the mean daily calcium intake in the case group was significantly lower than that in the control group (P<0.001).

Table 2 shows the mean serum calcium level in the two groups. The two groups had no significant difference in this regard (P=0.139).

Table 1. Comparison of the mean daily calcium intake (mg/day) between the two groups

Table 2. Comparison of the mean serum calcium level (mg/dL) between the two groups

Furthermore, the mean serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level in the case group was significantly lower than that in the control group (Table 3, P< 0.001).

Table 3. Comparison of the mean serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level (Nmol/L) between the two groups

A binary logistic regression model was used to adjust for the study variables. A crude regression was performed, and variables with P values less than 0.20 were initially selected. These variables were then entered into the regression model simultaneously to investigate the relationship between bruxism and the other variables while controlling for them. Finally, the serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D, daily calcium intake, and monthly income were entered into the regression model. The results indicated that after controlling for daily calcium intake in the binary logistic regression model, bruxism was significantly associated with vitamin D deficiency (odds ratio=1.170, P<0.001). However, when controlling for serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level, no statistically significant relationship was found between bruxism and daily calcium intake (odds ratio=1.006, P=0.056). There was a significant direct correlation between monthly income and serum calcium level (P=0.015, odds ratio=0.304) as well as serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level (P=0.024, odds ratio=0.281). This indicates that individuals with a higher monthly income tended to have significantly higher levels of both serum calcium and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (Table 4).

Discussion

Discussion

Vitamin D plays a crucial role in maintaining calcium balance in the body. A deficiency in vitamin D, which can lead to low calcium levels (hypocalcemia), may contribute to sleep bruxism by affecting the neuromuscular function [17]. Addressing this issue by replacing vitamin D and calcium levels could potentially aid in treatment of sleep bruxism. In this study, the mean daily calcium intake in the case group was 169.38±111.99 mg, which was significantly lower than that in the control group, which had a mean intake of 295.00±136.40 mg. Previous research has demonstrated a link between nutrition and nutrient intake with the occurrence of bruxism. For instance, Alkhatatbeh et al. [15] found that only 26% of patients with bruxism consumed more than 600 mg of calcium per day, compared to 42% of controls. Their findings indicated a significant correlation between low daily calcium intake and bruxism. The results of the present study are consistent with those reported by Alkhatatbeh et al. [15]. In the present study, the mean serum calcium level in the case group was found to be 8.87±0.75 mg/dL while the mean serum calcium level in the control group was 9.13±0.59 mg/dL. Although the case group had a lower mean calcium level, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups. Similarly, in a study conducted by Kanclerska et al, [18], the levels of several electrolytes, including serum calcium, were assessed in relation to the severity of tooth grinding. They reported no statistically significant difference in serum calcium concentration between individuals with sleep bruxism and the control group. The present findings are consistent with those of Kanclerska et al [18]. In the present study, the mean serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the case group was found to be 21.21±8.43 Nmol/L, which was significantly lower than that in the control group, which was 38.54±11.19 Nmol/L. This finding indicates an association between bruxism and vitamin D deficiency. Various studies have investigated the mean concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and the incidence of sleep bruxism [19-21]. The results of these studies consistently showed an inverse relationship between the concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and the incidence of bruxism. Individuals with sleep bruxism exhibited significantly lower serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

Table 4. Correlation coefficients for the association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, calcium level, daily calcium intake, and monthly income

Additionally, there appears to be a connection between low vitamin D levels and various sleep problems, including bruxism [9,19-21]. These findings align with the results of the present study. The results of this study indicated a significant and direct correlation between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, serum calcium levels, and daily calcium intake. It means that individuals with higher serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels also had significantly higher serum calcium levels and daily calcium intake.

Various studies have noted that low levels of vitamin D can disrupt calcium homeostasis and impact neuronal excitability [22-25]. Additionally, since vitamin D plays a crucial role in maintaining calcium balance, insufficient levels of vitamin D lead to a reduction in serum calcium levels (hypocalcemia) and muscle spasms and cramps, which aligns with the findings of the current study [22-25].

Anxiety, stress, and psychological factors have been identified as significant contributors to bruxism in numerous studies. Alkhatatbeh et al. [15] reported that individuals with bruxism exhibited higher levels of stress and anxiety compared to those without this condition. Additionally, a study by Allaf and Abdul-Hak [14] demonstrated that increased severity of vitamin D deficiency was associated with worsening of bruxism.

In the present study, however, an analysis of self-reported results from the Beck questionnaire revealed no significant differences in stress and anxiety levels between the control and case groups. These findings contradict the results of previous studies [15,23]. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in how stress levels are measured, variations in the statistical populations studied, and the smaller sample size of the current study.

This study suggested that individuals with higher monthly incomes tend to have significantly higher serum calcium and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. Two previous studies suggested that this disorder is more common among children from higher socioeconomic classes [26,27]. However, the results of the present study are inconsistent with earlier findings in this regard. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in the socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds of the target groups across various studies and countries. Socioeconomic and cultural characteristics may be linked to the prevalence of sleep bruxism [28].

This study had some limitations; for instance, the diagnosis of sleep bruxism was not confirmed through polysomnography, as this method is expensive, time-consuming, and unavailable at the study location. Thus, bruxism was assessed by using a validated questionnaire. This study can encourage others to investigate the potential cause-and-effect relationship between sleep bruxism, vitamin D deficiency, and low calcium levels. Additionally, further research is necessary to determine whether correcting vitamin D deficiency and increasing dietary calcium intake can alleviate the symptoms of sleep bruxism and provide practical suggestions for the treatment of this disorder.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicated that patients with bruxism had a significantly lower mean serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D compared to healthy controls. This suggests a strong association between bruxism and vitamin D deficiency. Furthermore, while individuals with bruxism showed a lower daily intake of calcium, the results revealed no statistically significant relationship between bruxism and daily calcium intake after controlling for the serum level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Additionally, there was no significant difference in the mean serum calcium levels between the case and control groups.

Type of Study: Original article |

Subject:

Oral medicine

References

1. Manfredini D, Winocur E, Guarda-Nardini L, Paesani D, Lobbezoo F. Epidemiology of bruxism in adults: a systematic review of the literature. J Orofac Pain. 2013 Spring; 27(2):99-110. [DOI:10.11607/jop.921]

2. Part A. Submission for Reclassification of Vitamin D. Report prepared by Medsafe. 2011 Dec;10-15.

3. Molina OF, Santos ZC, Simião BRH, Marchezan RF, e Silva NdP, Gama KR. A comprehensive method to classify subgroups of bruxers in temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) individuals: frequency, clinical and psychological implications. Rev. Sul-Bras. Odontol. 2013;10(1):11-9. [DOI:10.21726/rsbo.v10i1.888]

4. Jiang J, Tan H, Xia Z, Li J, Zhou S, Huang T. Serum vitamin D concentrations and sleep disorders: insights from NHANES 2011-2016 and Mendelian Randomization analysis. Sleep Breath. 2024 Aug;28(4):1679-90. [DOI:10.1007/s11325-024-03031-2] [PMID] []

5. Zhu C, Zhang Y, Wang T, Lin Y, Yu J, Xia Q, et al. Vitamin D supplementation improves anxiety but not depression symptoms in patients with vitamin D deficiency. Brain Behav. 2020 Nov;10(11):e01760. [DOI:10.1002/brb3.1760] [PMID] []

6. Shaffer JA, Edmondson D, Wasson LT, Falzon L, Homma K, Ezeokoli N, et al. Vitamin D supplementation for depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2014 Apr;76(3):190-6. [DOI:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000044] [PMID] []

7. Correia AS, Vale N. Tryptophan metabolism in depression: A narrative review with a focus on serotonin and kynurenine pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Jul;23(15):8493. [DOI:10.3390/ijms23158493] [PMID] []

8. Allami ZZ, ALkhalidi FK, Dragh MA. The correlations of vitamin D and zinc deficiency with neck pain, fatigue, and tremors of muscle: A case report and review of article. J Med Life Sci. 2024 Nov:471-9. [DOI:10.21608/jmals.2024.390104]

9. Alkhatatbeh MJ, Abdul-Razzak KK, Amara NA, Al-Jarrah M. Non-cardiac chest pain and anxiety: A possible link to vitamin D and calcium. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2019 Jun;26 (2):194-9. [DOI:10.1007/s10880-018-9579-2] [PMID]

10. Frosztega W, Wieckiewicz M, Nowacki D, Poreba R, Lachowicz G, Mazur G, et al. The effect of coffee and black tea consumption on sleep bruxism intensity based on polysomnographic examination. Heliyon. 2023 May;9(5):e16212. [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16212] [PMID] []

11. Herrero Babiloni A, Lavigne GJ. Sleep bruxism: A "bridge" between dental and sleep medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018 Aug;14(8):1281-3. [DOI:10.5664/jcsm.7254] [PMID] []

12. Flueraşu MI, Bocşan IC, Țig IA, Iacob SM, Popa D, Buduru S. The epidemiology of bruxism in relation to psychological factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jan;19(2):691. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19020691] [PMID] []

13. Jahanimoghadam F, Tohidimoghadam M, Poureslami H , Sharifi M. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Bruxism in a Selected Population of Iranian Children.Pesqui. Bras. Odontopediatria Clín. Integr. 2023 Jul;23:e210224. [DOI:10.1590/pboci.2023.020]

14. Allaf BAW, Abdul-Hak M. Association between bruxism severity and serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2022 Aug;8(4):827-35. [DOI:10.1002/cre2.530] [PMID] []

15. Alkhatatbeh MJ, Hmoud ZL, Abdul-Razzak KK, Alem EM. Self-reported sleep bruxism is associated with vitamin D deficiency and low dietary calcium intake: a case-control study. BMC Oral Health. 2021 Jan;21(1):21. [DOI:10.1186/s12903-020-01349-3] [PMID] []

16. Nahidi M, Ahmadi M, Fayyazi Bordbar MR, Morovatdar N, Khadem-Rezayian M, Abdolalizadeh A. The relationship between mobile phone addiction and depression, anxiety, and sleep quality in medical students. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2024 Mar;39(2):70-81. [DOI:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000517] [PMID]

17. Botelho J, Machado V, Proença L, Delgado AS, Mendes JJ. Vitamin D deficiency and oral health: A comprehensive review. Nutrients. 2020 May;12(5):1471. [DOI:10.3390/nu12051471] [PMID] []

18. Kanclerska J, Wieckiewicz M, Szymanska-Chabowska A, Poreba R, Gac P, Wojakowska A, et al. The relationship between the plasma concentration of electrolytes and intensity of sleep bruxism and blood pressure variability among sleep bruxers. Biomedicines. 2022 Nov;10(11):2804. [DOI:10.3390/biomedicines10112804] [PMID] []

19. Pavlou IA, Spandidos DA, Zoumpourlis V, Adamaki M. Nutrient insufficiencies and deficiencies involved in the pathogenesis of bruxism (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2023 Oct;26(6):563. [DOI:10.3892/etm.2023.12262] [PMID] []

20. de Menezes-Júnior LAA, Sabião TDS, de Moura SS, Batista AP, de Menezes MC, Carraro JCC, et al. Influence of sunlight on the association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and sleep quality in Brazilian adults: A population-based study. Nutrition. 2023 Jun;110:112008. [DOI:10.1016/j.nut.2023.112008] [PMID] []

21. Anjum I, Jaffery SS, Fayyaz M, Samoo Z, Anjum S. The role of vitamin D in brain health: A mini literature review. Cureus. 2018 Jul;10(7):e2960. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.2960]

22. Johnson MM, Patel S, Williams J. Don't take it 'lytely': A case of acute tetany. Cureus. 2019 Oct;11(10):e5845. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.5845]

23. Montero J, Gómez-Polo C. Personality traits and dental anxiety in self-reported bruxism. A cross-sectional study. J Dent. 2017 Oct;65:45-50. [DOI:10.1016/j.jdent.2017.07.002] [PMID]

24. Murtaza H, Ghaffar A. The Effect of Low Vitamin D Levels on Recurrent Muscle Cramps. J Biol Med Innov. 2025 Jun;3(1):1-2.

25. Menéndez SG, Manucha W. Vitamin D as a modulator of neuroinflammation: implications for brain health. Curr Pharm Des. 2024;30(5):323-32. [DOI:10.2174/0113816128281314231219113942] [PMID]

26. Machado E, Dal-Fabbro C, Cunali PA, Kaizer OB. Prevalence of sleep bruxism in children: a systematic review. Dental Press J Orthod. 2014 Nov-Dec;19(6):54-61. [DOI:10.1590/2176-9451.19.6.054-061.oar] [PMID] []

27. Serra-Negra JM, Paiva SM, Seabra AP, Dorella C, Lemos BF, Pordeus IA. Prevalence of sleep bruxism in a group of Brazilian schoolchildren. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2010 Aug;11(4):192-5. [DOI:10.1007/BF03262743] [PMID]

28. Bulanda S, Ilczuk-Rypuła D, Nitecka-Buchta A, Nowak Z, Baron S, Postek-Stefańska L. Sleep bruxism in children: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment-A literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Sep;18(18):9544. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18189544] [PMID] []

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |