Volume 10, Issue 4 (12-2025)

J Res Dent Maxillofac Sci 2025, 10(4): 299-309 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.IAU.PS.REC.1402.494

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Jadidi H, Azizi A, Safarzadeh Khosroshahi S, Ramezani G. Effect of Cold Plasma on Dentin Microshear Bond Strength of Primary Anterior Teeth. J Res Dent Maxillofac Sci 2025; 10 (4) :299-309

URL: http://jrdms.dentaliau.ac.ir/article-1-814-en.html

URL: http://jrdms.dentaliau.ac.ir/article-1-814-en.html

1- Department of Pediatric Dentistry, TeMS.C., Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Oral Medicine, TeMS.C., Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Restorative Dentistry, TeMS.C., Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

4- Department of Pediatric Dentistry, TeMS.C., Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran ,gh.h.ramezani@gmail.com

2- Department of Oral Medicine, TeMS.C., Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

3- Department of Restorative Dentistry, TeMS.C., Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

4- Department of Pediatric Dentistry, TeMS.C., Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran ,

Full-Text [PDF 548 kb]

(12 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (22 Views)

Full-Text: (5 Views)

Abstract

Background and Aim: Effective composite bonding to primary teeth is crucial. Cold plasma treatment could enhance this bonding. This study investigated the effect of cold atmospheric plasma on dentin microshear bond strength (µSBS) of primary anterior teeth.

Materials and Methods: In this in vitro study, 84 eligible primary anterior teeth were randomly assigned to six groups: (I) Adper Single Bond 2 fifth-generation bonding agent, (II) fifth-generation bonding agent + 15-second plasma treatment, (III) fifth-generation bonding agent + 30-second plasma treatment, (IV) Single Bond Universal adhesive, (V) universal adhesive + 15-second plasma treatment, and (VI) universal adhesive + 30-second plasma treatment. The µSBS test was then performed. Fracture mode was determined under a stereomicroscope. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and stereomicroscopic assessments were also performed. Data were analyzed by one-way and two-way ANOVA, and Tukey and t tests.

Results: The universal adhesive group had a significantly higher µSBS (39 MPa) than the fifth-generation bonding group (13.5 MPa). A significant difference existed between the no plasma and 30-second plasma treatment groups (P=0.001). In the universal groups, significant differences were noted between no plasma and both 15-second and 30-second treatments (P<0.05). Universal adhesive outperformed the fifth-generation bonding agent in the no plasma and 15-second treatment groups (P=0.007). Adhesive failures predominated in all groups, and SEM analysis showed distinct differences in dentinal tubules among the bonding systems.

Conclusion: It is recommended to use Single Bond Universal adhesive without plasma, and consider plasma treatment to enhance bonding in Adper Single Bond 2 fifth-generation system.

Keywords: Dental Bonding; Dentin-Bonding Agents; Plasma Gases; Therapeutic Use; Tooth, Deciduous

Introduction

Preservation of primary teeth is a critical goal in pediatric dentistry to ensure proper growth and development, coordination of dental arch, and occlusal balance [1]. Premature loss of primary teeth can lead to malocclusion, esthetic problems, speech problems, or temporary/permanent functional problems [2]. The growing emphasis on minimally invasive dentistry and increased awareness about esthetics necessitate the use of advanced restorative materials, such as composite restorations, in pediatric dentistry [3]. However, these materials come with certain disadvantages, including debonding of the composite from the tooth structure, which can lead to postoperative tooth hypersensitivity, secondary caries, and microleakage in composite restorations [4, 5]. Efficient bonding of restorative materials to both enamel and dentin in primary teeth is essential to preserve the tooth structure and enhance esthetics and durability. Bonding to dentin is more challenging than bonding to enamel due to its heterogeneous structure, which varies by type, location, and distance from the dentinoenamel junction. Bonding to primary dentin is particularly difficult because of its unique microstructure and chemical composition [3]. Different methods are available for preparation of tooth surfaces: phosphoric acid etching and rinsing (fourth and fifth generations), self-etch adhesives (sixth and seventh generations), and universal adhesives (eighth generation) [4, 6]. Considering the importance of time in behavioral management in pediatric dental procedures, single-step bonding agents are often preferred [6].

Cold atmospheric plasma has numerous biomedical applications since its contact temperature is below 40°C, minimizing damage to underlying healthy tissues [7]. Plasma treatment induces microstructural and chemical changes in the enamel and dentin, enhancing bonding and improving the interface with composite resins [8]. Short-term plasma treatment can alter the chemical structure of collagen fibers and increase the hydrophilicity of enamel, improving composite infiltration into the collagen fibers and significantly enhancing the bond between composite and dentin [9]. While studies on permanent teeth have demonstrated the positive effect of plasma on improving the bond strength of composite to tooth structure [10, 11], research on the impact of plasma on composite bonding to primary teeth is limited.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effect of cold atmospheric plasma on dentin microshear bond strength (µSBS) of primary anterior teeth. The null hypothesis of the study was that using cold atmospheric plasma would have no significant effect on dentin µSBS of primary anterior teeth.

Materials and Methods

This in vitro experimental study was conducted at Islamic Azad University in Tehran, Iran, from October 2023 to June 2024. The university's ethical committee approved the study (ethics code: IR.IAU.PS.REC.1402.494). Based on the results of a study by Wang et al. [12] and using one-way ANOVA power analysis feature of PASS 11, the minimum sample size required was determined to be 10 per group, assuming a significance level (alpha) of 0.05%, a beta error rate of 0.2%, a mean bond strength standard deviation of 6.2 MPa, and an effect size of 0.504. A total of 84 teeth were selected for the study based on the eligibility criteria.

The inclusion criteria were primary anterior teeth extracted due to orthodontic treatment or exfoliated due to root resorption with intact crowns. The exclusion criteria were teeth with caries, anomalies, or existing restorations. After extraction, the teeth were stored in 0.5% thymol (Mainolab, Iran) solution to inhibit bacterial growth until the day of the experiment. First, the roots were cut using a diamond fissure bur (Tizkavan, Iran) at low speed under water coolant 2-3 mm below the cementoenamel junction. The samples were mounted in acrylic resin blocks (Acropars, Tehran, Iran) with 0.5 mm height and 1 cm diameter. Then, the buccal surface dentin was exposed using 600-grit silicon carbide abrasive paper under water coolant. The teeth were then examined under a stereomicroscope (Nikon, Japan) at ×40 magnification to ensure the absence of enamel and no pulp exposure. The samples were then ultrasonically cleaned for 10 minutes to remove debris and stored in distilled water at 4°C throughout the study. The teeth were randomly divided into six groups of 14 as follows:

Group 1 (fifth-generation bonding agent): The teeth were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions as follows:

Background and Aim: Effective composite bonding to primary teeth is crucial. Cold plasma treatment could enhance this bonding. This study investigated the effect of cold atmospheric plasma on dentin microshear bond strength (µSBS) of primary anterior teeth.

Materials and Methods: In this in vitro study, 84 eligible primary anterior teeth were randomly assigned to six groups: (I) Adper Single Bond 2 fifth-generation bonding agent, (II) fifth-generation bonding agent + 15-second plasma treatment, (III) fifth-generation bonding agent + 30-second plasma treatment, (IV) Single Bond Universal adhesive, (V) universal adhesive + 15-second plasma treatment, and (VI) universal adhesive + 30-second plasma treatment. The µSBS test was then performed. Fracture mode was determined under a stereomicroscope. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and stereomicroscopic assessments were also performed. Data were analyzed by one-way and two-way ANOVA, and Tukey and t tests.

Results: The universal adhesive group had a significantly higher µSBS (39 MPa) than the fifth-generation bonding group (13.5 MPa). A significant difference existed between the no plasma and 30-second plasma treatment groups (P=0.001). In the universal groups, significant differences were noted between no plasma and both 15-second and 30-second treatments (P<0.05). Universal adhesive outperformed the fifth-generation bonding agent in the no plasma and 15-second treatment groups (P=0.007). Adhesive failures predominated in all groups, and SEM analysis showed distinct differences in dentinal tubules among the bonding systems.

Conclusion: It is recommended to use Single Bond Universal adhesive without plasma, and consider plasma treatment to enhance bonding in Adper Single Bond 2 fifth-generation system.

Keywords: Dental Bonding; Dentin-Bonding Agents; Plasma Gases; Therapeutic Use; Tooth, Deciduous

Introduction

Preservation of primary teeth is a critical goal in pediatric dentistry to ensure proper growth and development, coordination of dental arch, and occlusal balance [1]. Premature loss of primary teeth can lead to malocclusion, esthetic problems, speech problems, or temporary/permanent functional problems [2]. The growing emphasis on minimally invasive dentistry and increased awareness about esthetics necessitate the use of advanced restorative materials, such as composite restorations, in pediatric dentistry [3]. However, these materials come with certain disadvantages, including debonding of the composite from the tooth structure, which can lead to postoperative tooth hypersensitivity, secondary caries, and microleakage in composite restorations [4, 5]. Efficient bonding of restorative materials to both enamel and dentin in primary teeth is essential to preserve the tooth structure and enhance esthetics and durability. Bonding to dentin is more challenging than bonding to enamel due to its heterogeneous structure, which varies by type, location, and distance from the dentinoenamel junction. Bonding to primary dentin is particularly difficult because of its unique microstructure and chemical composition [3]. Different methods are available for preparation of tooth surfaces: phosphoric acid etching and rinsing (fourth and fifth generations), self-etch adhesives (sixth and seventh generations), and universal adhesives (eighth generation) [4, 6]. Considering the importance of time in behavioral management in pediatric dental procedures, single-step bonding agents are often preferred [6].

Cold atmospheric plasma has numerous biomedical applications since its contact temperature is below 40°C, minimizing damage to underlying healthy tissues [7]. Plasma treatment induces microstructural and chemical changes in the enamel and dentin, enhancing bonding and improving the interface with composite resins [8]. Short-term plasma treatment can alter the chemical structure of collagen fibers and increase the hydrophilicity of enamel, improving composite infiltration into the collagen fibers and significantly enhancing the bond between composite and dentin [9]. While studies on permanent teeth have demonstrated the positive effect of plasma on improving the bond strength of composite to tooth structure [10, 11], research on the impact of plasma on composite bonding to primary teeth is limited.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effect of cold atmospheric plasma on dentin microshear bond strength (µSBS) of primary anterior teeth. The null hypothesis of the study was that using cold atmospheric plasma would have no significant effect on dentin µSBS of primary anterior teeth.

Materials and Methods

This in vitro experimental study was conducted at Islamic Azad University in Tehran, Iran, from October 2023 to June 2024. The university's ethical committee approved the study (ethics code: IR.IAU.PS.REC.1402.494). Based on the results of a study by Wang et al. [12] and using one-way ANOVA power analysis feature of PASS 11, the minimum sample size required was determined to be 10 per group, assuming a significance level (alpha) of 0.05%, a beta error rate of 0.2%, a mean bond strength standard deviation of 6.2 MPa, and an effect size of 0.504. A total of 84 teeth were selected for the study based on the eligibility criteria.

The inclusion criteria were primary anterior teeth extracted due to orthodontic treatment or exfoliated due to root resorption with intact crowns. The exclusion criteria were teeth with caries, anomalies, or existing restorations. After extraction, the teeth were stored in 0.5% thymol (Mainolab, Iran) solution to inhibit bacterial growth until the day of the experiment. First, the roots were cut using a diamond fissure bur (Tizkavan, Iran) at low speed under water coolant 2-3 mm below the cementoenamel junction. The samples were mounted in acrylic resin blocks (Acropars, Tehran, Iran) with 0.5 mm height and 1 cm diameter. Then, the buccal surface dentin was exposed using 600-grit silicon carbide abrasive paper under water coolant. The teeth were then examined under a stereomicroscope (Nikon, Japan) at ×40 magnification to ensure the absence of enamel and no pulp exposure. The samples were then ultrasonically cleaned for 10 minutes to remove debris and stored in distilled water at 4°C throughout the study. The teeth were randomly divided into six groups of 14 as follows:

Group 1 (fifth-generation bonding agent): The teeth were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions as follows:

- Etching with 37% phosphoric acid (Scotchbond, 3M, USA) for 15 seconds.

- Rinsing for 10 seconds.

- Applying the bonding agent (Adper Single Bond 2, 3M, USA) on the specimen surface with a microbrush and waiting for 15 seconds.

- Applying gentle air pressure for 5 seconds.

- Curing for 10 seconds with a light-curing unit (Lied Plus, Woodpecker, China) with a light intensity of 500 mW/cm2.

- Application of composite resin (Filtek Z350, 3M ESPE, USA) in polyethylene Tygon tubes (Micro-bore Tygon Medical Tubing, Saint Gobain Performance Plastics, Akron, OH, USA) with 1 mm height and 0.9 mm internal diameter.

- Placing the Tygon tubes on the middle third of the buccal surface of the specimens and curing for 40 seconds as explained earlier.

- Separating the Tygon tubes using a #15 scalpel (Hi-Cut, India).

Group 2 (fifth-generation bonding agent + 15-second plasma treatment): The teeth were prepared as explained for group 1 and also underwent plasma treatment (Plasmart, Nariatech Co., Tehran, Iran) after rinsing the acid etchant and before the application of bonding agent as follows:

A plasma jet nozzle was used with 8 W input power, 4 mA intensity, and helium gas flow rate of 3.8 L/min for 15 and 30 seconds. The peak frequency and voltage were 50 Hz and 0.780 kV, respectively. The operator maintained a safe distance of 10 mm between the dentin surface and the nozzle.

Group 3 (fifth-generation bonding agent + 30-second plasma treatment): Similar to group 2, with the difference that plasma was applied for 30 seconds.

Group 4 (universal adhesive): The teeth were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions as follows:

A plasma jet nozzle was used with 8 W input power, 4 mA intensity, and helium gas flow rate of 3.8 L/min for 15 and 30 seconds. The peak frequency and voltage were 50 Hz and 0.780 kV, respectively. The operator maintained a safe distance of 10 mm between the dentin surface and the nozzle.

Group 3 (fifth-generation bonding agent + 30-second plasma treatment): Similar to group 2, with the difference that plasma was applied for 30 seconds.

Group 4 (universal adhesive): The teeth were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions as follows:

- Applying universal adhesive (Single Bond Universal, 3M, USA) on the specimen surface with a microbrush and waiting for 20 seconds.

- Applying gentle air pressure for 5 seconds.

- Curing for 10 seconds with a light-curing unit (Lied Plus, Woodpecker, China) at 500 mW/cm2.

- Application of composite resin (Filtek Z350, 3M ESPE, USA) in polyethylene Tygon tubes (Micro-bore Tygon Medical Tubing, Saint Gobain Performance Plastics, Akron, OH, USA), with 1 mm height and 0.9 mm internal diameter.

- Placing the Tygon tubes on the middle third of the buccal surface of the specimens and curing for 40 seconds with the same light intensity mentioned earlier [31].

- Separating the Tygon tubes using a #15 scalpel (Hi-Cut, India).

Group 5 (universal adhesive + 15-second plasma treatment): The teeth were prepared similarly to group 4, with a 15-second plasma treatment before the application of adhesive.

Group 6 (universal adhesive + 30-second plasma treatment): Similar to group 5, with the difference that plasma was applied for 30 seconds.

The specimens were then examined under a stereomicroscope (Nikon, Japan) at 25× magnification to assess bonding defects, air bubbles, or surface gaps.

Measurement of µSBS:

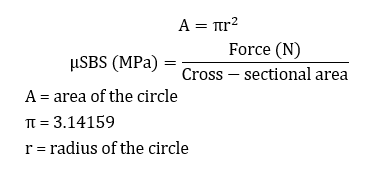

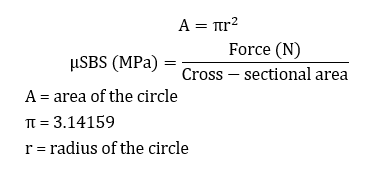

The μSBS was measured in a universal testing machine (Santam STM-20, Tehran, Iran) (Figure 1). A 0.2 mm orthodontic wire was looped around each specimen (in contact with half of the specimen), and load was applied at a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min until failure. The maximum force causing debonding was recorded in Newtons (N) and converted to megapascals (MPa) by dividing by the cross-sectional area of the specimens using the following formulae:

Figure 1. Measuring the µSBS

Stereomicroscopic assessment:

All specimens were examined under a stereomicroscope (Nikon, Japan) at ×40 magnification to determine the fracture mode.

Classification of the fracture mode was performed as follows:

Adhesive failure: The restorative material separates at the bonding interface, leaving adhesive material on both the tooth and within the dentinal tubules.

Cohesive failure: The failure occurs within the molecular bonds of a material, with the adhesive layer remaining both on the tooth and the restorative material.

Mixed failure: A combination of the above-mentioned two fracture types [13].

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM):

The samples, both with and without longitudinal sections, were observed under the following conditions: Two samples exhibiting adhesive failure were randomly selected from each group and subsequently divided into two subgroups, ensuring each subgroup contained one sample from each original group. In one subgroup, the specimens were longitudinally sectioned using a diamond disc. All samples were then polished sequentially, starting with a 1200-grit sandpaper, then 600-grit, and finally 400-grit sandpaper, with each polishing step lasting for 5 seconds. Following demineralization in 5% nitric acid for 20 minutes and immersion in 5% sodium hypochlorite solution for 20 minutes, the samples were rinsed, dried, and silver-coated. Morphological analysis of dentin surfaces was performed using SEM (VEGA II XMU, Germany) at ×1000 and ×5000 magnifications.

Statistical analysis:

SPSS version 29 (SPSS Inc., IL, USA) was utilized to perform one-way ANOVA, two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s HSD post hoc test, and t-test at 0.05 level of significance.

Results

The μSBS values of the 6 groups are summarized in Table 1. One-way ANOVA showed that the μSBS of group 4 (universal adhesive with 15-second plasma treatment) was significantly higher than that of group 1 (fifth-generation without plasma treatment). Considering the presence of two variables of plasma treatment and bonding agent, two-way ANOVA was also conducted, which yielded a P-value < 0.001. Normal data distribution justified the use of Tukey’s HSD post hoc test. The post hoc test results for the fifth-generation groups indicated no significant difference between the group without plasma and the group with 15-second plasma treatment (P>0.05). However, a significant difference was observed between the group without plasma and those with 30-second plasma treatment (P<0.05, Table 2). The post hoc test results for the universal adhesive groups indicated no significant difference between the two plasma treatment groups (P>0.05), but there was a significant difference between the group without plasma and the two other groups (P<0.05, Table 2). T-test was performed to compare two different adhesives in the groups with and without plasma treatment for 15 and 30 seconds (Table 3). In the no plasma and 15-second plasma treatment groups, the universal adhesive groups showed significantly higher μSBS values (P=0.007), and there was no significant difference between the two bonding agents with 30-second plasma treatment (P=0.779).

Table 4 show the results of the stereomicroscopic assessment. Adhesive failure was the most common failure mode across all groups.

Figures 2-4 present the SEM results. The dentinal tubules were not detectable on the images of the samples with longitudinal sections. In comparison of the two different bonding agents, the fifth-generation bonding agent showed fewer dentinal tubules with a smaller diameter; while the universal adhesive group exhibited more distinct dentinal tubule openings. In using the fifth-generation bonding agent, the 30-second plasma treatment resulted in fewer and smaller dentinal tubule openings. There was no significant difference in morphology among different groups when universal adhesive was used.

Table 1. Mean µSBS (MPa) of the six groups (n=14)

Figure 2. SEM images of specimen surface after adhesive bond failure at 5000x magnificaion. A: Fifth-generation, group 1. B: Universal adhesive, group 4

Figure 3. SEM images of specimen surface of the fifth-generation groups. A: no plasma treatment. B: 15-second plasma treatment. C: 30-second plasma treatment

Figure 4. SEM images of specimen surface of the universal groups. A: No plasma treatment. B: 15-second plasma treatment. C: 30-second plasma treatment

Table 2. Pairwise comparisons of plasma treatment effects on bond strength for the fifth-generation bonding agent and universal adhesive

Table 3. T-test results for the comparison of the two adhesives (n=14)

Table 4. Stereomicroscopic assessment results regarding the failure mode frequency (n=14)

Discussion

Given the importance of composite bond strength to teeth, various methods have been introduced to enhance bonding, one of the newest being the use of atmospheric pressure cold plasma [14]. This study evaluated the effect of plasma treatment on dentin µSBS in primary anterior teeth. Based on the present results, application of plasma in the universal adhesive group significantly decreased the µSBS compared to the universal adhesive group alone, but there was no difference between the 15- and 30-second plasma treatment groups. In fifth-generation bonding agent groups, plasma treatment significantly increased the µSBS. Specifically, there was no difference between the group without plasma and the 15-second plasma treatment group, but there was a difference with the 30-second group, indicating that the effectiveness of plasma increased with time. Therefore, the null hypothesis was rejected.

Cold plasma, also known as non-thermal atmospheric plasma, can enhance bonding and improve adhesion to composite resins by causing microstructural and chemical changes in etched enamel and dentin surfaces [9]. Previous research has reported the positive effects of plasma on µSBS [14]. Plasma treatment generates free radicals and high-energy photons, which can cause changes in the substrate surface, increase surface energy and hydrophilicity [15], and reduce excess dentin moisture without degrading or demineralizing the collagen matrix [10]. Studies have also reported that cold plasma removes the organic content from dentin by breaking carbon-carbon and carbon-hydrogen bonds and releasing hydroxyl groups [16, 17]. This process can enhance bonding by increasing interactions between the electron groups and hydrogen bonds in the adhesive system and dentin [18]. Various factors, such as the type of gas used in the plasma (helium or argon) [19], plasma exposure duration [12], distance from the tooth surface [20], timing of plasma irradiation in relation to the bonding procedure [10], and constituents of different bonding systems, can influence the effect of plasma on bond strength. Based on previous studies, this study selected the irradiation protocol with a duration of 15 and 30 seconds, at 10 mm distance from the tooth surface, and plasma application before the bonding procedure [12, 20, 21]. Due to the conflicting results of previous studies regarding the duration of treatment, both 15 and 30-second intervals were examined in this study. Inconsistent with the present study, Wang et al. [12] concluded that applying plasma before the bonding procedure increased the SBS of composite to permanent teeth using an eighth-generation bonding agent, with the maximum SBS reported at 15 seconds. This difference in the results could be attributed to different methodologies, as their study used plasma with argon gas, which has different characteristics from helium, including a higher electron temperature and lower electron density [22]. Such differences can affect the plasma's ability to modify the dentin surface and enhance adhesion in composite restorations [23]. Additionally, in the study by Wang et al. [12], SE Bond (Kuraray, Tokyo, Japan) was used as the bonding agent, which contains different components, including hydrophilic amide monomers that create numerous cross-links and dissolve the smear layer and allow for high adhesive monomer penetration. In contrast, Single Bond Universal used in the current study contains phosphoric acid and silane, which enhance its wetting capacity and facilitate the penetration of the adhesive system [24, 25]. This combination allows the adhesive to permeate dentin smears and effectively impregnate the underlying dentin [26]. In contrast to the current study, they observed dentinal tubules in samples with longitudinal sections. However, in the present study, SEM assessment of the samples with longitudinal sections was not feasible due to the small size of primary teeth. In the study by Wang et al. [12], an improvement in SBS was observed when using plasma with a fifth-generation bonding agent; however, increasing the plasma exposure time was associated with a decrease in SBS, which was in contrast to the present findings. According to a study by Strazzi-Sahyon et al. [17], prolonged plasma exposure time can degrade collagen fibrils by enhancing the etching effect and potentially affect the long-term durability of restorations. Consistent with the current study, Bolla et al. [10] found that plasma treatment after etching and before bonding in fifth-generation bonding agents increased the SBS. However, contrary to the present findings, plasma treatment before the bonding process was associated with increased SBS in using a universal adhesive. The difference in the results could be due to the differences in machine settings and plasma exposure protocols, including higher energy of plasma, closer distance to the tooth surface, and intermittent plasma exposure at 5-second intervals. They found that plasma irradiation after adhesive application was associated with a reduction in bond strength, and consistent with this study, the effect of plasma on improving the bond strength was reported to be better with the total-etch system compared to universal adhesive. In a study by Ayres et al. [27], a two-year follow-up demonstrated that plasma application with a 30-second protocol significantly increased the SBS in the etch-and-rinse group, while no significant difference was observed in the universal adhesive group. Moreover, in a systematic review, Awad et al. [14] reported that plasma effectively enhanced the SBS with the etch-and-rinse system. However, the universal adhesive did not show a distinct impact, highlighting the need for further studies using consistent protocols. Bond strength relies significantly on forming adequate resin tags and a compact, homogeneous hybrid layer. The smear layer, composed of organic materials and mineral remnants formed during enamel cutting, occludes the dentinal tubules [28]. The etch-and-rinse systems effectively remove the smear layer using phosphoric acid, creating a non-mineralized dentin surface that enhances adhesive penetration into collagen and forms a thick hybrid layer. In contrast, universal systems reach the underlying dentin without eliminating the smear layer, achieving penetration with acidic monomers that leave dentin non-mineralized, and form a thin hybrid layer [29]. A wide range of SBS values has been reported in the literature, with universal systems exceeding 30 MPa and fifth-generation total-etch systems achieving 25 MPa [30]. A recent study also showed that the immediate SBS of universal systems was lower than that of etch-and-rinse systems but comparable after 24 hours [31]. Aligned with the current results, Chauhan et al. [32] reported higher bond strength of an eighth-generation bonding agent compared to a fifth-generation dentin bonding agent, potentially due to the high technical sensitivity of fifth-generation systems and degradation of dentinal tubules and collagen fibers during the etching and drying phases. Meanwhile, the bond strength of the eighth-generation bonding agent was enhanced with the addition of nanofillers and 10-MDP monomers, which increase substance penetration into the tubules and chemical bonding to hydroxyapatite, respectively; thereby, improving long-term bonding durability [33]. Despite various studies highlighting the effects of plasma on aspects such as dentin surface modification [34, 35], dentin hydrophilicity [36], improvement of monomer polymerization [37], and enhancement of hybrid layer integrity in etch-and-rinse systems [27], it appears that plasma surface modification before bonding in eighth-generation universal systems may have altered the bonding interaction with dentin due to their distinct bonding mechanisms with dentin. This could stem from microstructural changes, including collagen fibril degradation, affecting monomer penetration. Additionally, universal systems penetrate into the smear layer, and plasma treatment may modify this smear layer [38], potentially influencing the bonding efficacy of eighth-generation universal systems.

The SEM results assessing the qualitative morphology of resin-dentin interface in the universal groups showed no significant difference between plasma-treated and untreated groups. However, in the etch-and-rinse groups, plasma application and longer treatment duration led to changes in the number and diameter of tubules consistent with prior research findings [14, 39]. Nevertheless, the interpretation of adhesive penetration into dentin remains contentious [40]. Hence, it cannot solely explain the positive impact of plasma on resin-dentin bond strength. This study provided valuable insights into the effects of 15- and 30-second plasma treatments and the impact of plasma on the bonding of adhesive systems to primary teeth.

This study had several limitations. First, it did not include contact angle measurements to validate the surface energy changes, which may influence the bonding performance. Second, the use of extracted teeth did not account for the influence of pulpal fluid pressure, which could affect resin infiltration and bond strength under clinical conditions. Additionally, due to the small size of primary teeth, it was challenging to obtain reliable longitudinal sections for SEM analysis, limiting the evaluation of resin tag formation. Although previous studies suggest that plasma treatment may enhance hybrid layer thickness in etch-and-rinse systems [27], this study could not comprehensively assess the hybrid layer due to the limited cross-sectional SEM evaluation. Future research should incorporate contact angle measurements, simulate intraoral fluid dynamics, and use improved sectioning techniques to better investigate the effects of plasma treatment on resin-dentin bonding.

Conclusion

Considering the limitations of this in vitro study, it was shown that Single Bond Universal adhesive provided the highest µSBS; while Adper Single Bond 2 etch-and-rinse system yielded the lowest µSBS. Plasma treatment significantly decreased the µSBS in both 15-second and 30-second protocols when using the universal adhesive, with no difference between these durations. In using the etch-and-rinse adhesive, only the 30-second plasma protocol significantly increased the µSBS compared to controls. It can be concluded that for optimal results, Single Bond Universal adhesive should be used without plasma treatment; while for Adper Single Bond 2 fifth-generation system, plasma treatment may enhance the bond strength.

Group 6 (universal adhesive + 30-second plasma treatment): Similar to group 5, with the difference that plasma was applied for 30 seconds.

The specimens were then examined under a stereomicroscope (Nikon, Japan) at 25× magnification to assess bonding defects, air bubbles, or surface gaps.

Measurement of µSBS:

The μSBS was measured in a universal testing machine (Santam STM-20, Tehran, Iran) (Figure 1). A 0.2 mm orthodontic wire was looped around each specimen (in contact with half of the specimen), and load was applied at a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min until failure. The maximum force causing debonding was recorded in Newtons (N) and converted to megapascals (MPa) by dividing by the cross-sectional area of the specimens using the following formulae:

Figure 1. Measuring the µSBS

Stereomicroscopic assessment:

All specimens were examined under a stereomicroscope (Nikon, Japan) at ×40 magnification to determine the fracture mode.

Classification of the fracture mode was performed as follows:

Adhesive failure: The restorative material separates at the bonding interface, leaving adhesive material on both the tooth and within the dentinal tubules.

Cohesive failure: The failure occurs within the molecular bonds of a material, with the adhesive layer remaining both on the tooth and the restorative material.

Mixed failure: A combination of the above-mentioned two fracture types [13].

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM):

The samples, both with and without longitudinal sections, were observed under the following conditions: Two samples exhibiting adhesive failure were randomly selected from each group and subsequently divided into two subgroups, ensuring each subgroup contained one sample from each original group. In one subgroup, the specimens were longitudinally sectioned using a diamond disc. All samples were then polished sequentially, starting with a 1200-grit sandpaper, then 600-grit, and finally 400-grit sandpaper, with each polishing step lasting for 5 seconds. Following demineralization in 5% nitric acid for 20 minutes and immersion in 5% sodium hypochlorite solution for 20 minutes, the samples were rinsed, dried, and silver-coated. Morphological analysis of dentin surfaces was performed using SEM (VEGA II XMU, Germany) at ×1000 and ×5000 magnifications.

Statistical analysis:

SPSS version 29 (SPSS Inc., IL, USA) was utilized to perform one-way ANOVA, two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s HSD post hoc test, and t-test at 0.05 level of significance.

Results

The μSBS values of the 6 groups are summarized in Table 1. One-way ANOVA showed that the μSBS of group 4 (universal adhesive with 15-second plasma treatment) was significantly higher than that of group 1 (fifth-generation without plasma treatment). Considering the presence of two variables of plasma treatment and bonding agent, two-way ANOVA was also conducted, which yielded a P-value < 0.001. Normal data distribution justified the use of Tukey’s HSD post hoc test. The post hoc test results for the fifth-generation groups indicated no significant difference between the group without plasma and the group with 15-second plasma treatment (P>0.05). However, a significant difference was observed between the group without plasma and those with 30-second plasma treatment (P<0.05, Table 2). The post hoc test results for the universal adhesive groups indicated no significant difference between the two plasma treatment groups (P>0.05), but there was a significant difference between the group without plasma and the two other groups (P<0.05, Table 2). T-test was performed to compare two different adhesives in the groups with and without plasma treatment for 15 and 30 seconds (Table 3). In the no plasma and 15-second plasma treatment groups, the universal adhesive groups showed significantly higher μSBS values (P=0.007), and there was no significant difference between the two bonding agents with 30-second plasma treatment (P=0.779).

Table 4 show the results of the stereomicroscopic assessment. Adhesive failure was the most common failure mode across all groups.

Figures 2-4 present the SEM results. The dentinal tubules were not detectable on the images of the samples with longitudinal sections. In comparison of the two different bonding agents, the fifth-generation bonding agent showed fewer dentinal tubules with a smaller diameter; while the universal adhesive group exhibited more distinct dentinal tubule openings. In using the fifth-generation bonding agent, the 30-second plasma treatment resulted in fewer and smaller dentinal tubule openings. There was no significant difference in morphology among different groups when universal adhesive was used.

Table 1. Mean µSBS (MPa) of the six groups (n=14)

Figure 2. SEM images of specimen surface after adhesive bond failure at 5000x magnificaion. A: Fifth-generation, group 1. B: Universal adhesive, group 4

Figure 3. SEM images of specimen surface of the fifth-generation groups. A: no plasma treatment. B: 15-second plasma treatment. C: 30-second plasma treatment

Figure 4. SEM images of specimen surface of the universal groups. A: No plasma treatment. B: 15-second plasma treatment. C: 30-second plasma treatment

Table 2. Pairwise comparisons of plasma treatment effects on bond strength for the fifth-generation bonding agent and universal adhesive

Table 3. T-test results for the comparison of the two adhesives (n=14)

Table 4. Stereomicroscopic assessment results regarding the failure mode frequency (n=14)

Discussion

Given the importance of composite bond strength to teeth, various methods have been introduced to enhance bonding, one of the newest being the use of atmospheric pressure cold plasma [14]. This study evaluated the effect of plasma treatment on dentin µSBS in primary anterior teeth. Based on the present results, application of plasma in the universal adhesive group significantly decreased the µSBS compared to the universal adhesive group alone, but there was no difference between the 15- and 30-second plasma treatment groups. In fifth-generation bonding agent groups, plasma treatment significantly increased the µSBS. Specifically, there was no difference between the group without plasma and the 15-second plasma treatment group, but there was a difference with the 30-second group, indicating that the effectiveness of plasma increased with time. Therefore, the null hypothesis was rejected.

Cold plasma, also known as non-thermal atmospheric plasma, can enhance bonding and improve adhesion to composite resins by causing microstructural and chemical changes in etched enamel and dentin surfaces [9]. Previous research has reported the positive effects of plasma on µSBS [14]. Plasma treatment generates free radicals and high-energy photons, which can cause changes in the substrate surface, increase surface energy and hydrophilicity [15], and reduce excess dentin moisture without degrading or demineralizing the collagen matrix [10]. Studies have also reported that cold plasma removes the organic content from dentin by breaking carbon-carbon and carbon-hydrogen bonds and releasing hydroxyl groups [16, 17]. This process can enhance bonding by increasing interactions between the electron groups and hydrogen bonds in the adhesive system and dentin [18]. Various factors, such as the type of gas used in the plasma (helium or argon) [19], plasma exposure duration [12], distance from the tooth surface [20], timing of plasma irradiation in relation to the bonding procedure [10], and constituents of different bonding systems, can influence the effect of plasma on bond strength. Based on previous studies, this study selected the irradiation protocol with a duration of 15 and 30 seconds, at 10 mm distance from the tooth surface, and plasma application before the bonding procedure [12, 20, 21]. Due to the conflicting results of previous studies regarding the duration of treatment, both 15 and 30-second intervals were examined in this study. Inconsistent with the present study, Wang et al. [12] concluded that applying plasma before the bonding procedure increased the SBS of composite to permanent teeth using an eighth-generation bonding agent, with the maximum SBS reported at 15 seconds. This difference in the results could be attributed to different methodologies, as their study used plasma with argon gas, which has different characteristics from helium, including a higher electron temperature and lower electron density [22]. Such differences can affect the plasma's ability to modify the dentin surface and enhance adhesion in composite restorations [23]. Additionally, in the study by Wang et al. [12], SE Bond (Kuraray, Tokyo, Japan) was used as the bonding agent, which contains different components, including hydrophilic amide monomers that create numerous cross-links and dissolve the smear layer and allow for high adhesive monomer penetration. In contrast, Single Bond Universal used in the current study contains phosphoric acid and silane, which enhance its wetting capacity and facilitate the penetration of the adhesive system [24, 25]. This combination allows the adhesive to permeate dentin smears and effectively impregnate the underlying dentin [26]. In contrast to the current study, they observed dentinal tubules in samples with longitudinal sections. However, in the present study, SEM assessment of the samples with longitudinal sections was not feasible due to the small size of primary teeth. In the study by Wang et al. [12], an improvement in SBS was observed when using plasma with a fifth-generation bonding agent; however, increasing the plasma exposure time was associated with a decrease in SBS, which was in contrast to the present findings. According to a study by Strazzi-Sahyon et al. [17], prolonged plasma exposure time can degrade collagen fibrils by enhancing the etching effect and potentially affect the long-term durability of restorations. Consistent with the current study, Bolla et al. [10] found that plasma treatment after etching and before bonding in fifth-generation bonding agents increased the SBS. However, contrary to the present findings, plasma treatment before the bonding process was associated with increased SBS in using a universal adhesive. The difference in the results could be due to the differences in machine settings and plasma exposure protocols, including higher energy of plasma, closer distance to the tooth surface, and intermittent plasma exposure at 5-second intervals. They found that plasma irradiation after adhesive application was associated with a reduction in bond strength, and consistent with this study, the effect of plasma on improving the bond strength was reported to be better with the total-etch system compared to universal adhesive. In a study by Ayres et al. [27], a two-year follow-up demonstrated that plasma application with a 30-second protocol significantly increased the SBS in the etch-and-rinse group, while no significant difference was observed in the universal adhesive group. Moreover, in a systematic review, Awad et al. [14] reported that plasma effectively enhanced the SBS with the etch-and-rinse system. However, the universal adhesive did not show a distinct impact, highlighting the need for further studies using consistent protocols. Bond strength relies significantly on forming adequate resin tags and a compact, homogeneous hybrid layer. The smear layer, composed of organic materials and mineral remnants formed during enamel cutting, occludes the dentinal tubules [28]. The etch-and-rinse systems effectively remove the smear layer using phosphoric acid, creating a non-mineralized dentin surface that enhances adhesive penetration into collagen and forms a thick hybrid layer. In contrast, universal systems reach the underlying dentin without eliminating the smear layer, achieving penetration with acidic monomers that leave dentin non-mineralized, and form a thin hybrid layer [29]. A wide range of SBS values has been reported in the literature, with universal systems exceeding 30 MPa and fifth-generation total-etch systems achieving 25 MPa [30]. A recent study also showed that the immediate SBS of universal systems was lower than that of etch-and-rinse systems but comparable after 24 hours [31]. Aligned with the current results, Chauhan et al. [32] reported higher bond strength of an eighth-generation bonding agent compared to a fifth-generation dentin bonding agent, potentially due to the high technical sensitivity of fifth-generation systems and degradation of dentinal tubules and collagen fibers during the etching and drying phases. Meanwhile, the bond strength of the eighth-generation bonding agent was enhanced with the addition of nanofillers and 10-MDP monomers, which increase substance penetration into the tubules and chemical bonding to hydroxyapatite, respectively; thereby, improving long-term bonding durability [33]. Despite various studies highlighting the effects of plasma on aspects such as dentin surface modification [34, 35], dentin hydrophilicity [36], improvement of monomer polymerization [37], and enhancement of hybrid layer integrity in etch-and-rinse systems [27], it appears that plasma surface modification before bonding in eighth-generation universal systems may have altered the bonding interaction with dentin due to their distinct bonding mechanisms with dentin. This could stem from microstructural changes, including collagen fibril degradation, affecting monomer penetration. Additionally, universal systems penetrate into the smear layer, and plasma treatment may modify this smear layer [38], potentially influencing the bonding efficacy of eighth-generation universal systems.

The SEM results assessing the qualitative morphology of resin-dentin interface in the universal groups showed no significant difference between plasma-treated and untreated groups. However, in the etch-and-rinse groups, plasma application and longer treatment duration led to changes in the number and diameter of tubules consistent with prior research findings [14, 39]. Nevertheless, the interpretation of adhesive penetration into dentin remains contentious [40]. Hence, it cannot solely explain the positive impact of plasma on resin-dentin bond strength. This study provided valuable insights into the effects of 15- and 30-second plasma treatments and the impact of plasma on the bonding of adhesive systems to primary teeth.

This study had several limitations. First, it did not include contact angle measurements to validate the surface energy changes, which may influence the bonding performance. Second, the use of extracted teeth did not account for the influence of pulpal fluid pressure, which could affect resin infiltration and bond strength under clinical conditions. Additionally, due to the small size of primary teeth, it was challenging to obtain reliable longitudinal sections for SEM analysis, limiting the evaluation of resin tag formation. Although previous studies suggest that plasma treatment may enhance hybrid layer thickness in etch-and-rinse systems [27], this study could not comprehensively assess the hybrid layer due to the limited cross-sectional SEM evaluation. Future research should incorporate contact angle measurements, simulate intraoral fluid dynamics, and use improved sectioning techniques to better investigate the effects of plasma treatment on resin-dentin bonding.

Conclusion

Considering the limitations of this in vitro study, it was shown that Single Bond Universal adhesive provided the highest µSBS; while Adper Single Bond 2 etch-and-rinse system yielded the lowest µSBS. Plasma treatment significantly decreased the µSBS in both 15-second and 30-second protocols when using the universal adhesive, with no difference between these durations. In using the etch-and-rinse adhesive, only the 30-second plasma protocol significantly increased the µSBS compared to controls. It can be concluded that for optimal results, Single Bond Universal adhesive should be used without plasma treatment; while for Adper Single Bond 2 fifth-generation system, plasma treatment may enhance the bond strength.

Type of Study: Original article |

Subject:

pediatric

References

1. Nowak AJ. Pediatric Dentistry: Infancy Through Adolescence. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2019.

2. Shah S. Paediatric dentistry- novel evolvement. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2017 Dec 14;25:21-29. [DOI:10.1016/j.amsu.2017.12.005] [PMID] []

3. Kumar RK, Subramani SK, Swathika B, Ganesan S, Chikkanna M, Murugesan S, et al. Comparison of shear bond strength of composite resin, compomer, and resin-modified glass-ionomer cements in primary teeth: An in-vitro study. J Orthod Sci. 2023 Nov 2;12:71. [DOI:10.4103/jos.jos_36_23]

4. Adeyeye A, Spivey V, Stoeckel D, Welch D. Comparison of the marginal microleakage of a bioactive composite resin and traditional dental restorative materials. Gen Dent. 2023 May-Jun;71(3):52-56.

5. Mishra A, Koul M, Upadhyay VK, Abdullah A. A Comparative Evaluation of Shear Bond Strength of Seventh- and Eighth-Generation Self-etch Dentin Bonding Agents in Primary Teeth: An In Vitro Study. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2020 May-Jun;13(3):225-9. [DOI:10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1765] [PMID] []

6. Yamauchi K, Tsujimoto A, Jurado CA, Shimatani Y, Nagura Y, Takamizawa T, et al. Etch-and-rinse vs self-etch mode for dentin bonding effectiveness of universal adhesives. J Oral Sci. 2019 Nov 27;61(4):549-53. [DOI:10.2334/josnusd.18-0433] [PMID]

7. Laroussi M. Cold plasma in medicine and healthcare: The new frontier in low temperature plasma applications. Frontiers in Physics. 2020 Mar 20;8:74. [DOI:10.3389/fphy.2020.00074]

8. Zhu XM, Zhou JF, Guo H, Zhang XF, Liu XQ, Li HP, et al. Effects of a modified cold atmospheric plasma jet treatment on resin-dentin bonding. Dent Mater J. 2018 Sep 30;37(5):798-804. [DOI:10.4012/dmj.2017-314] [PMID]

9. Ritts AC, Li H, Yu Q, Xu C, Yao X, Hong L, et al. Dentin surface treatment using a non-thermal argon plasma brush for interfacial bonding improvement in composite restoration. Eur J Oral Sci. 2010 Oct;118(5):510-6. [DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0722.2010.00761.x] [PMID] []

10. Bolla N, Mayana AB, Gali PK, Vemuri S, Garlapati R, Kamal SA. Effect of nonthermal atmospheric plasma on bond strength of composite resin using total-etch and self-etch adhesive systems. J Conserv Dent. 2023 May-Jun;26(3):292-8. [DOI:10.4103/jcd.jcd_33_23] [PMID] []

11. Kim YM, Lee HY, Lee HJ, Kim JB, Kim S, Joo JY, Kim GC. Retention Improvement in Fluoride Application with Cold Atmospheric Plasma. J Dent Res. 2018 Feb;97(2):179-83. [DOI:10.1177/0022034517733958] [PMID] []

12. Wang DY, Wang P, Xie N, Yan XZ, Xu W, Wang LM, et al. In vitro study on non-thermal argon plasma in improving the bonding efficacy between dentin and self-etch adhesive systems. Dent Mater J. 2022 Jul 30;41(4):595-600. [DOI:10.4012/dmj.2021-215] [PMID]

13. Can-Karabulut DC, Oz FT, Karabulut B, Batmaz I, Ilk O. Adhesion to primary and permanent dentin and a simple model approach. Eur J Dent. 2009 Jan;3(1):32-41. [DOI:10.1055/s-0039-1697403] [PMID] []

14. Awad MM, Alhalabi F, Alshehri A, Aljeaidi Z, Alrahlah A, Özcan M, et al. Effect of Non-Thermal Atmospheric Plasma on Micro-Tensile Bond Strength at Adhesive/Dentin Interface: A Systematic Review. Materials (Basel). 2021 Feb 22;14(4):1026. [DOI:10.3390/ma14041026] [PMID] []

15. Thammajak P, Louwakul P, Srisuwan T. Effects of cold atmospheric pressure plasma jet on human apical papilla cell proliferation, mineralization, and attachment. Clin Oral Investig. 2021 May;25(5):3275-83. [DOI:10.1007/s00784-020-03659-w] [PMID]

16. Chen M, Zhang Y, Sky Driver M, Caruso AN, Yu Q, Wang Y. Surface modification of several dental substrates by non-thermal, atmospheric plasma brush. Dent Mater. 2013 Aug;29(8):871-80. [DOI:10.1016/j.dental.2013.05.002] [PMID] []

17. Strazzi-Sahyon HB, Suzuki TYU, Lima GQ, Delben JA, Cadorin BM, Nascimento VD, et al. In vitro study on how cold plasma affects dentin surface characteristics. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2021 Nov;123:104762. [DOI:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2021.104762] [PMID]

18. Stasic JN, Selaković N, Puač N, Miletić M, Malović G, Petrović ZL, et al. Effects of non-thermal atmospheric plasma treatment on dentin wetting and surface free energy for application of universal adhesives. Clin Oral Investig. 2019 Mar;23(3):1383-96. [DOI:10.1007/s00784-018-2563-2] [PMID]

19. Seo YS, Mohamed AA, Woo KC, Lee HW, Lee JK, Kim KT. Comparative studies of atmospheric pressure plasma characteristics between He and Ar working gases for sterilization. IEEE transactions on plasma science. 2010 Aug 5;38(10):2954-62. [DOI:10.1109/TPS.2010.2058870]

20. Stasic JN, Pficer JK, Milicic B, Puač N, Miletic V. Effects of non-thermal atmospheric plasma on dentin wetting and adhesive bonding efficiency: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent. 2021 Sep;112:103765. [DOI:10.1016/j.jdent.2021.103765] [PMID]

21. Zhu MM, Wang GM, Sun K, Li YL, Pan J. Bonding strength of resin and tooth enamel after teeth bleaching with cold plasma. Beijing da xue xue bao. Yi xue ban= Journal of Peking University. Health Sciences. 2016 Feb 1;48(1):116-20.

22. Jonkers J, Van De Sande M, Sola A, Gamero A, Van Der Mullen J. On the differences between ionizing helium and argon plasmas at atmospheric pressure. Plasma Sources Science and Technology. 2002 Dec 23;12(1):30. [DOI:10.1088/0963-0252/12/1/304]

23. Hoffmann C, Berganza C, Zhang J. Cold Atmospheric Plasma: methods of production and application in dentistry and oncology. Med Gas Res. 2013 Oct 1;3(1):21. [DOI:10.1186/2045-9912-3-21] [PMID] []

24. de Oliveira RP, de Paula BLF, Alencar CM, Alves EB, Silva CM. A randomized clinical study of the performance of self-etching adhesives containing HEMA and 10-MDP on non-carious cervical lesions: A 2-year follow-up study. J Dent. 2023 Mar;130:104407. [DOI:10.1016/j.jdent.2022.104407] [PMID]

25. Ren Z, Wang R, Zhu M. Comparative evaluation of bonding performance between universal and self-etch adhesives: In vitro study. Heliyon. 2024 Jul 26;10(15):e35226. [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35226] [PMID] []

26. Oliveira SS, Pugach MK, Hilton JF, Watanabe LG, Marshall SJ, Marshall GW Jr. The influence of the dentin smear layer on adhesion: a self-etching primer vs. a total-etch system. Dent Mater. 2003 Dec;19(8):758-67. [DOI:10.1016/S0109-5641(03)00023-X] [PMID]

27. Ayres AP, Freitas PH, De Munck J, Vananroye A, Clasen C, Dias CDS, Giannini M, Van Meerbeek B. Benefits of Nonthermal Atmospheric Plasma Treatment on Dentin Adhesion. Oper Dent. 2018 Nov/Dec;43(6):E288-E299. [DOI:10.2341/17-123-L] [PMID]

28. Dong X, Li H, Chen M, Wang Y, Yu Q. Plasma treatment of dentin surfaces for improving self-etching adhesive/dentin interface bonding. Clin Plasma Med. 2015 Jun 1;3(1):10-16. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpme.2015.05.002] [PMID] []

29. Tyas MJ, Burrow MF. Adhesive restorative materials: a review. Aust Dent J. 2004 Sep;49(3):112-21; quiz 154. [DOI:10.1111/j.1834-7819.2004.tb00059.x] [PMID]

30. Sofan E, Sofan A, Palaia G, Tenore G, Romeo U, Migliau G. Classification review of dental adhesive systems: from the IV generation to the universal type. Ann Stomatol (Roma). 2017 Jul 3;8(1):1-17. [DOI:10.11138/ads/2017.8.1.001] [PMID] []

31. Harnirattisai C, Roengrungreang P, Rangsisiripaiboon U, Senawongse P. Shear and micro-shear bond strengths of four self-etching adhesives measured immediately and 24 hours after application. Dent Mater J. 2012;31(5):779-87. [DOI:10.4012/dmj.2012-013] [PMID]

32. Chauhan U, Dewan R, Goyal NG. Comparative evaluation of bond strength of fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth generations of dentin bonding agents: an in vitro study. Journal of Operative Dentistry & Endodontics. 2020 Dec 1;5(2):69-73. [DOI:10.5005/jp-journals-10047-0103]

33. Hidari T, Takamizawa T, Imai A, Hirokane E, Ishii R, Tsujimoto A, et al. Role of the functional monomer 10-methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate in dentin bond durability of universal adhesives in etch-&-rinse mode. Dent Mater J. 2020 Aug 2;39(4):616-23. [DOI:10.4012/dmj.2019-154] [PMID]

34. Dong X, Chen M, Wang Y, Yu Q. A Mechanistic study of Plasma Treatment Effects on Demineralized Dentin Surfaces for Improved Adhesive/Dentin Interface Bonding. Clin Plasma Med. 2014 Jul 1;2(1):11-16. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpme.2014.04.001] [PMID] []

35. Mirhashemi A, Sharifi N, Kharazifard MJ, Jadidi H, Chiniforush N. Comparison of the adhesive remnant index and shear bond strength of orthodontic brackets using acid etch versus Er: YAG laser treatments. Laser Physics. 2019 Sep 30;29(11):115602. [DOI:10.1088/1555-6611/ab427e]

36. Kong MG, Kroesen G, Morfill G, Nosenko T, Shimizu T, Van Dijk J, et al. Plasma medicine: an introductory review. new Journal of Physics. 2009 Nov 1;11(11):115012. [DOI:10.1088/1367-2630/11/11/115012]

37. Kim JH, Han GJ, Kim CK, Oh KH, Chung SN, Chun BH, et al. Promotion of adhesive penetration and resin bond strength to dentin using non-thermal atmospheric pressure plasma. Eur J Oral Sci. 2016 Feb;124(1):89-95. [DOI:10.1111/eos.12246] [PMID]

38. Ayres AP, Bonvent JJ, Mogilevych B, Soares LES, Martin AA, Ambrosano GM, et al. Effect of non-thermal atmospheric plasma on the dentin-surface topography and composition and on the bond strength of a universal adhesive. Eur J Oral Sci. 2018 Feb;126(1):53-65. [DOI:10.1111/eos.12388] [PMID]

39. Xiaoming ZH, Heng GU, Jianfeng ZH, Jian CH, Jing LI, Heping LI, et al. Influences of the cold atmospheric plasma jet treatment on the properties of the demineralized dentin surfaces. Plasma Science and Technology. 2018 Mar 1;20(4):044010. [DOI:10.1088/2058-6272/aaa6be]

40. Langer A, Ilie N. Dentin infiltration ability of different classes of adhesive systems. Clin Oral Investig. 2013 Jan;17(1):205-16. [DOI:10.1007/s00784-012-0694-4] [PMID]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |